WORDS BYPankaj Singh

PHOTOGRAPHY BYRamya Reddy

Listen to this story. Narrated by Pankaj Singh. Soundscape by Naveed Mulki.

He spoke too softly. She spoke too little. It was because where he lived, the land was so silent that people needed only to speak in whispers to be heard. Where she spent most of her time, speaking was unnecessary. Her eyes spoke sentences punctuated by delicately moving arms.

When we exchanged greetings, his firm hands held mine just a little longer. In his land, visitors were few. He had known and felt the cold winter’s breath one would have endured before arriving at his doorstep. His hands were the first offering of warmth. Her embrace was weak yet loving. She had learnt in the blue underworld, one must learn to let go. That, like with water, the more one tried to draw closer, the more one lost. Her weak embrace was an offering of this wisdom.

He walked with a gentle, deliberate lean. Not because he was old. This was owed in reverence to the giants in whose shadows he had always walked. Her gait was weightless and without the burden of self-importance. Like she barely acknowledged her existence. In the blue abyss where she roamed, light was so feeble, she never saw her own shadow – and what was a thing that didn’t cast shadows?

I met them both in a city. Far from their homes. We were strangers; silent in each other’s presence. But in just a few moments, in just a few words, in him I had met the mountains, in her, the ocean.

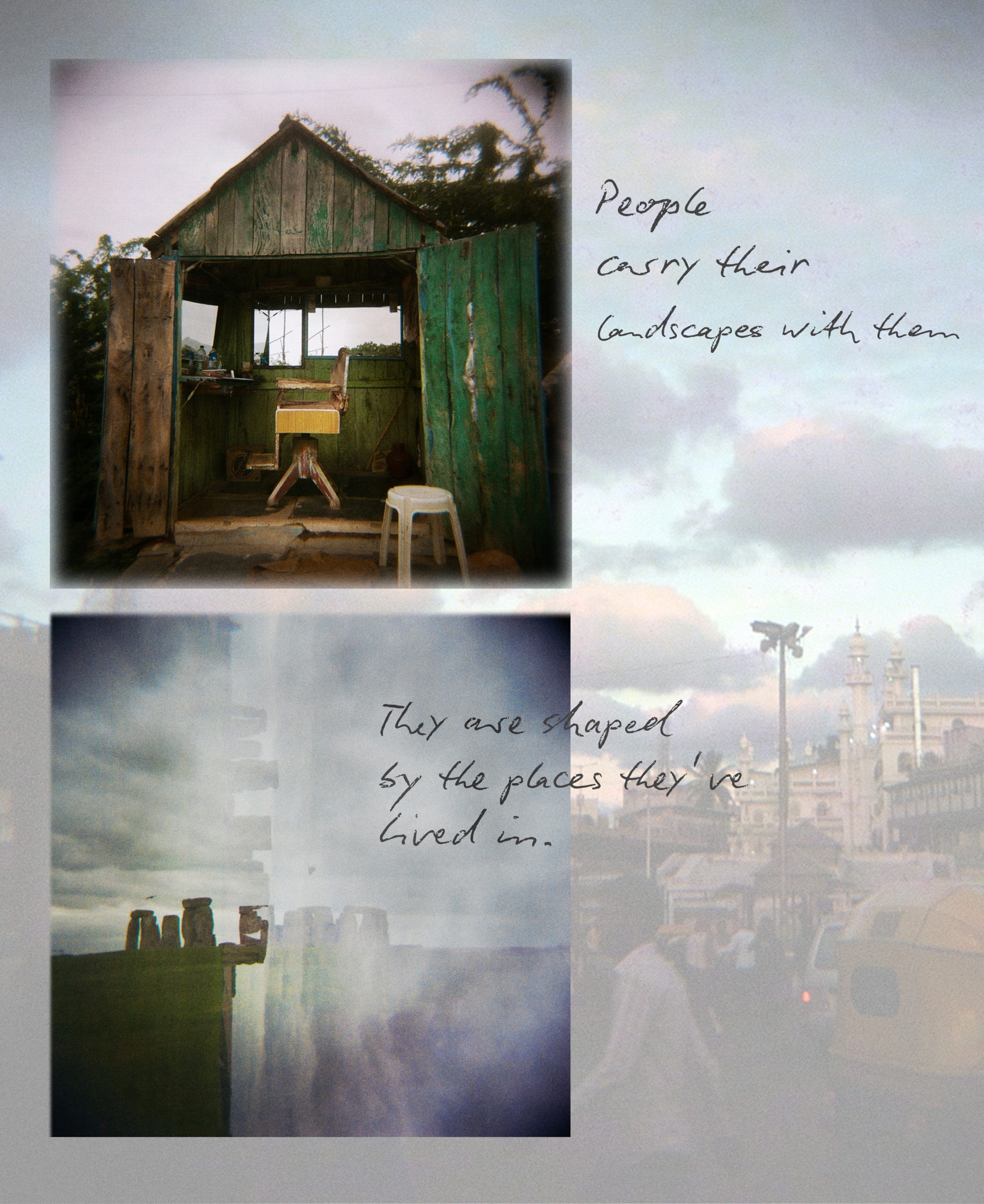

People carry their landscapes with them – of this I am certain. They are shaped by the places they’ve lived in.

The seascapes and the dunes, the forests and the mountains, the rivers and the desert plains, the hills and the valleys, the towns and cityscapes imprint themselves in their inhabitants and trail them like shadows, wherever they go.

I met the river Indus in a man of seventy and more. He was born by the river in a house by its rocky banks. He spoke louder than most because in that house, a conversation was possible only if one spoke above the sound of the river’s flow. We met in a tent-café in eastern Ladakh. He sat beside me but spoke aloud. As if he were shouting to someone across the road. He was speaking above the sound of the river that was raging some hundred kilometres away. Between sentences, when he paused to think, I could hear the Indus.

I met the chaos and disorder of Varanasi in a man who had his bike mirrors angled inward . “Out of habit”, he told me and I understood. Visiting in 2016, I remember being rattled by the frenzy that coursed through the narrow alleys of this ancient city. Bikers zipped to and fro like pinballs in timelapse. Choosing the generous utility of the horn above the breaks. Having the mirrors angled outward meant certain collision. There was only so much room to get around. And speed, like light speed had to remain constant. Moving among the soft natured, easy-going crowd of Bangalore, he rode furiously with the frames screwed inward; holding a mirror to a heart that didn’t belong.

I met the monsoons of Kerala in the umbrella hung on the back of a shirt collar in Delhi. This man from Wayanad, at the slightest indication of the weather turning, would hang his umbrella at the back of his collar and step outside, arms crossed at the back. “Never know how bad it can get.”

Trees are said to fare better in communities – in groves and forests where their roots underground converse and make exchanges of nutrients and information. In the event of life-threatening damage, the root system, if intact, is nursed back to good health by the trees surrounding, so it may restore itself and regrow into the canopy that sustains a favourable microclimate. Transplant a tree from a collective existence to a place without other trees, without a forest to be part of and it will almost certainly become more vulnerable to infections, to diseases and storms.

Humans share about 50% of their DNA with trees. The banyan, the magnolia, the Ficus, the raintree and our bipedal forms share a common ancestor. I don’t know if this accounts for the part of us that wants to arrive at a place and take seed, establish roots, bonds, belong to our own forest of conversing trees.

Just like the regions of mountains and oceans that shape our characters, our inner landscapes have a way of spilling outward and impressing our stories in the spaces we dwell in:

Sideways notches made along doorframes, marked with dates to record height growth, a smudge-cloud of hair oil on the wall from all the times someone we knew rested their heads against the wall when the television came on, faint outlines of action-hero stickers peeled from the windowpanes, almirahs and refrigerators. A strip of bindis left behind a mirror and forgotten. Empty drawers still smelling of camphor and incense. An unstruck match placed absent-mindedly beside the chimney – every object, every feature and every tangible detail is tied to the memory of a particular time in our lives in that place.

And then, some spaces become so inseparably entangled with a memory, there is little room for the remembrance of any other unfolding. You pass by a large building and recognize this one particular lighted window. Here, it is always 2 am. Here, the air always rings with the urgently repeating syllables that made up the name of somebody you knew, who they tried to bring back. To you, this is a place where time does not elapse. It refuses to spill from that second into the next. It is always 2 am. And the memory plays itself to infinity like a vacation advert looped on a flight full of passengers deep asleep.

Not every seed becomes a tree. Some fail to find nurture and germinate. Some remain dormant, patiently waiting for favourable times while some never break out their shells to meet the sun. “Failure to germinate”; the inability to belong, is sadly a predicament we often find ourselves in, when existing in spaces that don’t allow us grow into the full breadth of our beings. This is when we go searching for any loose fragments of belonging that offer comfort, even momentarily.

In Junagarh, Gujarat, I overheard a video conversation between a Tamilzh-speaking storekeeper and his grandson who was going to visit him from Coimbatore.

“Thatha, You are sure you don’t want anything else?”, the grandson asked.

“News papers…just the local news papers. As many as you can get.”

“Any particular piece of news you are looking for? Any particular publication?”

“Get whatever you can, how many ever you can. Topic or date doesn’t matter… Son, I just want to read Tamil.”

While some find strands of home in the reaching arms of language, others may find it in a plain old recipe:

A potato salad that the world couldn’t care less about. But to you, every notion of home and belonging came to rest in the simple act of washing mud off the potatoes in preparation. Everytime it was made, as ingredients came together, it felt like a time, a person, a place, a feeling, a universe you longed for began to piece itself back around you, atom by atom.

Few things say “I belong here” in the way that trees do. Some people want to be like trees while some want to be tumbleweed.

Tumbleweed, by design, have a layer of cells called the abscission layer. The purpose of this layer is to facilitate complete severance of the plant from the root system. A clean break allows the tumbleweed to roll off on a journey that can span hundreds of miles, anywhere the wind blows.

Like one Mr. O, the young man on a fruit-diet, who I met in the Palani hills – everything that made up his life back in Europe had the same presence as one of those cardboard boxes filled with miscellaneous objects that you pack but choose to leave behind when you move out of a house. He had left behind a life of excess, addiction and abuse and wanted nothing to do with it. He had shed it down to the last leaf and stepped out to meet the world.

Sometimes , consciously and successfully “Forgetting” , “Overcoming”, “Cauterizing”, is only half the job done. The bitter drink of grief and pain, even when emptied from our cups, leaves behind dregs.

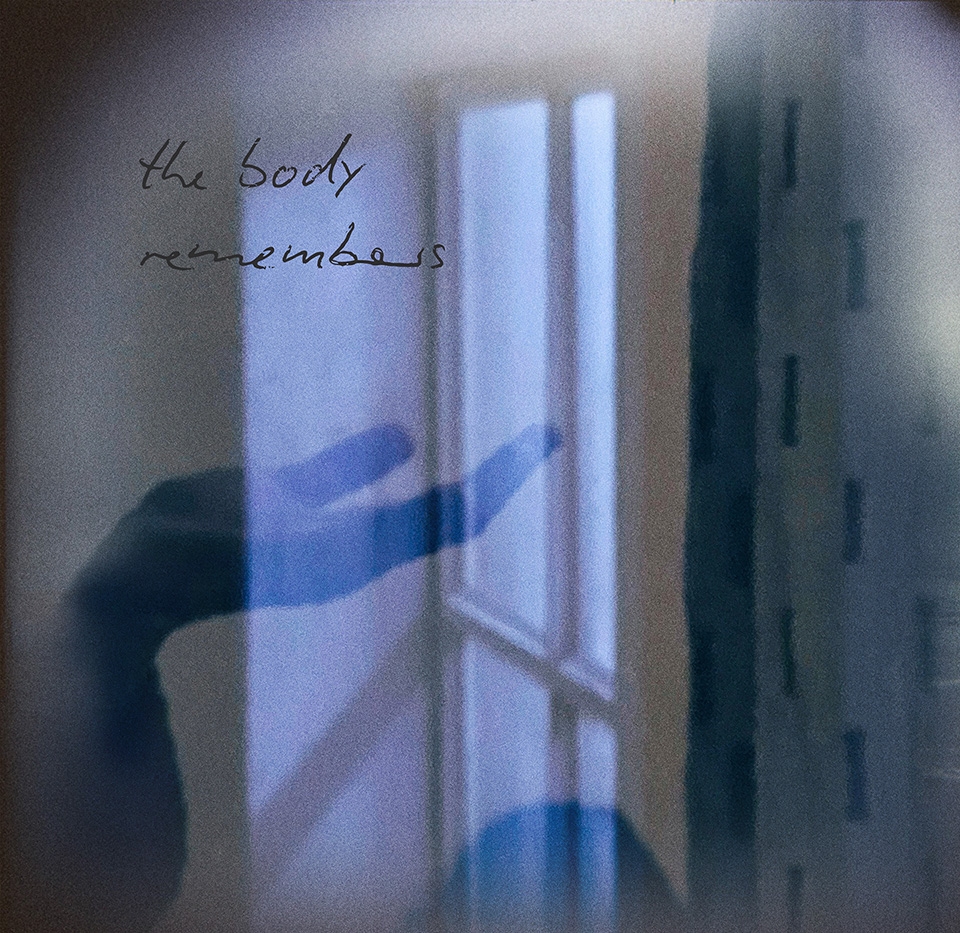

We often forget that the body remembers what the heart wants to forget. That the body too is a place where the deepest feelings, emotions and memories reside. That though we flush them from our minds and our hearts, they can cling to the periphery of our beings, in skin, and scar. In reflex and sensation.

In Ladakh, on a winding mountain road snaking above a river, the bus I was in toppled on its side. A flimsy railing saved the bus from falling over. But I lost a friend. The trauma of the accident and of witnessing a death are long overcome. I feel a passing sadness at best, when I think of the young boy who was called Chospel. But even now, 5 years on, feeling the momentum as the car even slightly swerves on a bend throws the body into state of paralysing fear. The body remembers.

It isn’t improbable to believe that the body grieves in its own ways. Anybody who has said goodbye to a loved one recognises the times when waves of grief come barreling through their being unexpectedly. Remembering, mourning somebody gone feels distinctly different than your physical being missing how time and space felt around a person. How on walks, the feet fell into a familiar cadence that you shared with this person alone, how silence was registered, how breath was drawn from and returned to the universe.

What strange stories we live; Sleepwalking through the spaces that exist between remembering and forgetting, between longing and belonging, between arriving, staying, leaving behind.

Perhaps we will do well to navigate the complexities of the human life by learning from the simple lives of migrating birds. Specifically, a Bar-tailed godwit chick named B6. Born in Alaska, this youngling fattened up in over three months before setting off on a lonely journey as winter set in. Leaving the shores of Nome, Alaska, for the very first time, B6 flew over the frigid waters of the Pacific ocean through storm, hail and strong winds. A day became two, two became four and a mint-sized tag on its back continued pinging information about its whereabouts above the ocean to researchers. The flight path remained steady and relayed that B6 was flying without any rest stops or feeding breaks. The Bar-tailed godwit chick flew across the ocean without stops until it arrived at Tasmania (13,560 kilometres), after 11 days of continuous flight. This is the longest recorded bird flight ever.

Why did this little assemblage of feathers, hollow bones and beak soar headlong into one of the most incredible adventures in the animal kingdom?

Like every other migrating creature, B6 had simply followed an inner compass to a fertile land. An inner compass that had tugged at its being until making that flight was the only thing left to do. There was no room for doubt or second guessing. A voice had called and B6 had simply listened.

Isn’t that somehow, within us all too? Encoded in our genetic information – the desire to seek out, venture and arrive at a place that we can call home.

To dear friends and strangers, who are in between places, who are on their way, those who have little to long for and more to leave behind, those who find themselves stuck, the ones that “failed to germinate”, those who always dream of elsewhere places, those who don’t know where to go and the ones that do but don’t know how to – my deepest wish for them is that they be granted the grace of being allowed to listen to the voice that has always, always called to them. Just like this little godwit that trusted the voice enough to shrink its organs in order to sustain the longest flight ever recorded, simply to arrive in a place of warmth and nurture.

I wish that they allow that soft tug, that inner compass to lead them to the true north of their existence.