WORDS BYSharanya Manivannan

ILLUSTRATIONS BYRamya Reddy

It has been years since I have been in the mountains, yet I only feel this fact if I pause to count. The mountains are always inside me, lining the safe spaces in my mind. Perhaps this comforting certainty is only a clutch of, and a clutching to, memories.

Specific evocations gathered over a lifetime – the way facing backwards in an open-top vehicle changed how the winding road curved around the bends and how the fields below revealed their emerald and umber expanses; a particular sill on which I sat and watched the rain as I grappled with a knowing that was somehow both thorny and soft to hold; the late afternoon lavished on a sudden sighting of an elephant treading through tea bushes, so the sunset vista that had been my destination was forgotten until the light began to give out; the crisp, dew-laden air and the promise that the first morning after an arrival always contains. They seem like only memories, if I try to describe them, but to me they are like drawers or rooms: opened, everything they contain is exactly where it should be. The greater part of me that roams or languishes elsewhere, at sea level or in skyscrapers or both, is rarely exactly where it should be. Yet within the imprints the mountains have on me are a sentiment that always tethers me to a sense of my own true north. Those remnants, those reminiscences: they feel like a home.

To carry the mountains into the other scapes that you must inhabit, by will or by circumstance, is a practice of remembering and meditation. It begins, as most great loves do, with longing.

Let this longing steep, like a brew, so that it disperses its essence into the fabric of your daily life. Both tangibly – objects within reach and sight, visual renderings – and intangibly – scents, poetry – there are ways to keep the mountains close.

Let this longing steep, like a brew, so that it disperses its essence into the fabric of your daily life. Both tangibly – objects within reach and sight, visual renderings – and intangibly – scents, poetry – there are ways to keep the mountains close.

There is a poem I know apocryphally – which is to say, I wish I could quote its lines in translation and that I knew who had written them down to begin with, but I do not. I know of the poem because I understand its meaning, because the writer Elizabeth Gilbert has spoken to her own audiences about this meaning. My description of this Japanese poem, held in memory over the years even though Gilbert’s re-rendered words have long dissipated, goes thus – a monk stands at the crest of the mountain and sees everything the valley and the sky contain. He sees everything. And then, he returns to the plains and to the ordinary rhythms of existence – carrying the mountaintop beneath his robes.

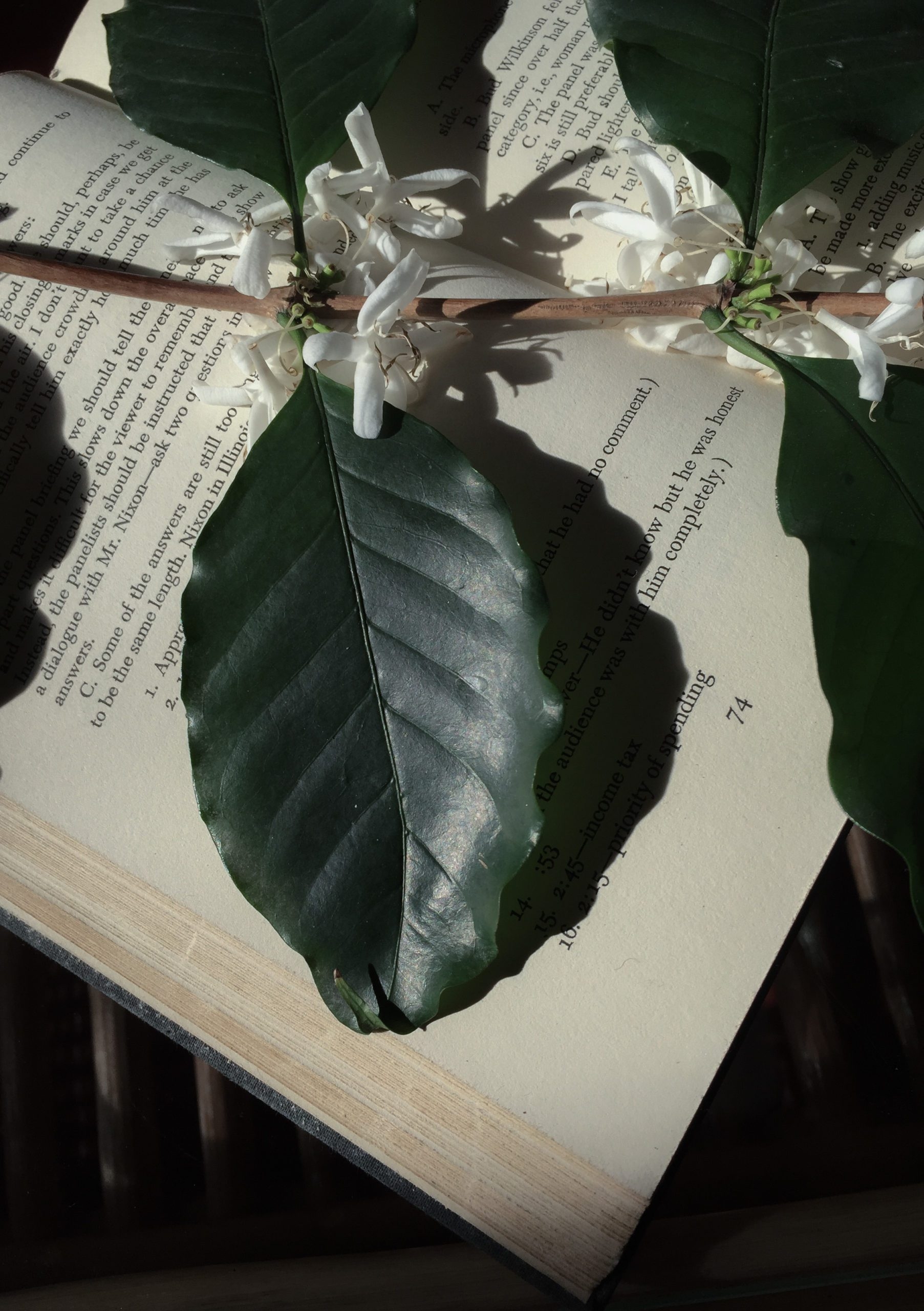

In telling this poem in my own words, a poem I may not ever have read myself, I have made a version of it that I want to hold on to. That is one way to do it: to press a place between the pages of our lives like a flower. And let it disperse its quintessence all over the crags and glens of our quotidian lives.

Find the secret ways in which to make them stay, ways only you know. A bookmark, a dried fern in a frame, a pebble in the pocket, the opening chords of a certain tune, a fragrant balm, a harvest that has travelled a distance still bearing the touch of the hands that raised it.

In telling this poem in my own words, a poem I may not ever have read myself, I have made a version of it that I want to hold on to. That is one way to do it: to press a place between the pages of our lives like a flower. And let it disperse its quintessence all over the crags and glens of our quotidian lives.

Find the secret ways in which to make them stay, ways only you know. A bookmark, a dried fern in a frame, a pebble in the pocket, the opening chords of a certain tune, a fragrant balm, a harvest that has travelled a distance still bearing the touch of the hands that raised it.

So, from a distance, we keep the mountains within us alive and within reach. We may not be in them, but they are in us.

Some of these ways will be in sight of others (and if they are perceptive, they’ll recognize that what they have is a glimpse into your soul too). Don’t be surprised if people notice, if they sense that you are mountain-kindred, or if you too – in some strange, sweet way – become a part of their own secret pathways to linger, through the heart and the imagination, in a beautiful mountain milieu.

(Written several weeks before the author returned, with pleasure, to the mountains…)