Of Renewal Through Nourishment

Listen to this story. Narrated by Amrita Amesur.

I find that the women of my generation, millennials, especially in India with the relative privilege of receiving higher education have grown up in the chasm of two colliding worlds. One pulling us into fierce independence, seeking power and agency to be at the top of our professional game. Whereas the other still steeped in notions of Indian traditionalism, expected to cook, clean and marry well and reproduce promptly. Dedicating ourselves to professional pursuits never excluded the societal expectations of adhering to every traditionally mandated tenet.

Never has a generation of women had to do as much a breadth of activities to justify their entering of the labour market as us – from securing the best exam scores, chasing high paying jobs, balancing housework and caregiving with the demands of professional commitment. We must burn the candle at both ends – rationalize to the office why as a woman you’re worth taking on despite your period pains and ticking biological clock and then justify at home why you must work to gain financial security while also balancing household responsibilities. All the while competing with men, who themselves have created these structures and rules that govern our realms, giving them every advantage and encouragement to excel through their socially superior upbringing, whether in education or at the office. It’s very easy to succeed in a world tailor made for you and when the labour of caregiving is relegated simply to “the Women”.

In this hostile climate, where the guillotine of forced arranged marriages was always at the risk of dropping on our necks, financial independence became the singular way to achieve any semblance of control and agency on our own lives. Consequently, that involved staying as far away from the kitchen as possible. The oppressively gendered kitchen environment that our mothers lived in was a looming threat to the life we aspired to have. Sadly, what we lost in this bargain was the very basic ability to feed and nourish ourselves. Because cooking was always meant to be a larger service performed by women for their families and community, often eating only once others have finished and picking at whatever’s leftover. Lack of adequate nutrition affects women disproportionately due to biological, social and cultural factors in India making women vulnerable, especially during childbirth and lactation. While women live longer than men, studies show that women are more sickly and disabled than men throughout their life cycle 1. Women’s disproportionate poverty, low socioeconomic status, gender discrimination and reproductive role not only expose them to various diseases, but also their access to and use of health services 2. The highest incidence of malnutrition among women is reported in South Asia.3 Being a woman in India is nothing short of a Sisyphean task where the boulder must be pushed by us uphill everyday, only for it to fall back down again. The burden of prejudices that our generation, especially men, carry about cooking being something only our moms and/or wives do and the misnomer of it not being as essential as learning to walk or speak, has rendered them debilitated to feed themselves. It has in turn imprisoned women to the stove, turning the pure joy of cookery and self-nourishment to lifelong servitude.

When I turned 30, I sought to reverse the trend. I set out to learn to cook, but only for myself.

Not for my father who saw it as a means for me to be a qualified wife and child bearer for my future husband, not professionally to prove some sort of career change to the world, but simply as an act of self-nourishment. As a way to provide delicious wholesome meals for myself, at will, without dependance or compromise. It was my pursuit of joy and regeneration of my soul through food sovereignty. A way to work with my hands and mindfully create things that would enter my body. This change of my praxis from transactions, contracts, interpretation and analysis as a lawyer, to working with my hands, trusting my senses as is necessary in cooking instead of the written word or measures, has been transformational in opening up a part of me I didn’t know existed. Cooking became my singular purpose, as a means to understand myself, come to terms with my past, live my tumultuous present and welcome my unforeseen future. A method by which to dissect world cultures, identities and the deep-rooted social inequalities I encountered daily as a woman.

The first thing I consciously learned to cook, as I set about upon this endeavour: my mother’s Monday dal. It’s the food I’ve taken for granted, been immensely bored with Monday after Monday but which has held me at chokehold ever since I learned to make it. Deceptively simple, it refuses to be made passively or in an unfocused manner, it demands attention, a keen olfactory sense and sharp tastebuds – a veritable balancing act of flavours and textures- which if ignored would render it inedible. This dal which I’ve made every week for over 3 years now, reins me back to my humble learnings as a daughter and a cook.

The cumin seeds in the tadka must be deeply darkly browned but not burnt and never fair, there should be no fewer than 4 (sometimes 5) souring and tart agents, added in at various stages of cooking, a pop of colour in the blanket of the turmeric hued dal with a few fresh bits of chopped tomato, a light brothy but incredibly smooth consistency that my friends have taken to calling “dal soup”, the pungency must come from grassy fresh green chillies and not dried chili powder. All of these must balance against the salt to make it pungent, tart, bright, light and still deeply comforting. From the mundane-ness of Monday dal, I now find myself craving its layered puckering tartness, as the pressures of Mondays set in.

At each of these cooking stages, your senses are your best friends. They must be alive and discerning – the scent of browned jeera versus burnt jeera, the mouthfeel of smooth brothy dal versus grainy or gritty, the aromas or the lack thereof telling you how much more salt it needs to come alive, the underlying acidity of curry leaves balancing against the tart kokum, sweet tomatoes and sharp limes. The moment you choose to take these cues for granted is when the dal is lost.

In this discernment as I cook this dal lies years of passivity, years of uncaring consumption that I must confront. The years of taking simple meals like these along with the labour of my mother for granted. There’s no amount of gratitude that can be enough to thank all the women that came before me, gave up their own nourishment such that I could be whole today. The only way I could even attempt to honour this was by learning how to cook for myself, seek nourishment and renewal from their teachings. In this path I shed every insecurity and inadequacy that was foisted on me by society, I became more of myself and less of Them. The ability to feed myself instilled a quiet confidence in the knowledge that I’m self-sufficient and no matter who comes and goes away from my life, I will always be able to self-nourish.

And if you master this dal, maybe you will too.

Mom’s Toor Dal Recipe

Yields 4-5 bowls of dal

Ingredients:

In the pressure cooker –

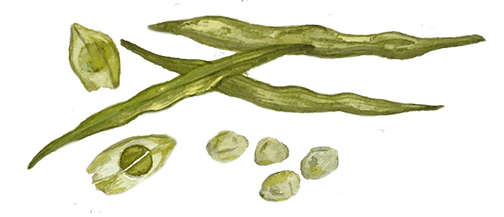

- 1/2 cup – Toor / Arhar dal or Dried split pigeon peas

- 1 stick of Moringa pods or drumsticks, cut into 3-4 pieces (optional)

- 1.5 cups of water

- Salt to taste

- ½ inch finely grated ginger

- 3 pungent green chillies cut into chunks

For finishing –

- 3-4 petals of dried/salted preserved kokum or 1 tablespoon of pure kokum extract.

- 1 tsp turmeric powder

- A sprig of fresh curry leaves

- 1 chopped up small tomato or half of a large tomato

- Juice of half a lime

- Chopped Coriander leaves for garnish

For tempering –

- 2-3 tablespoons of any preferred vegetable oil for tadka

- 1/2 tsp jeera/cumin seeds

- 1/4 tsp hing or asafoetida

Method:

- In a large bowl, measure out the toor dal and wash, swirl with hand and drain the water a few times until water is mostly clear. Fill fresh water into the bowl and soak the dal for at least 45-60 minutes. This tenderises and hydrates the dal, helping it cook more evenly. It also helps shed the naturally occurrent phytic acid in lentils so ensure optimum absorption of nutrition from the dal.

- Once finished soaking, drain out the water and tip in the dal into a pressure cooker along with chunks of chillies, Moringa pods (if using), grated ginger, enough salt to season the dal and water to cover about 3-4 inches above the dal. Pressure cook on high until dal is entirely cooked through, about 5-6 whistles in standard large cookers. Turn off the flame and let the pressure release naturally for another 10-15 minutes before opening the cooker.

- In the meantime, soak the kokum petals in a small bowl with hot water until it leaks out its purple juices and tart flavours.

- Separately, assemble the chopped tomatoes, curry leaves, lime juice and coriander.

- Once the dal is cooked, fish out the chunks of green chillies which have given out all their heat and also the moringa pods (if using). Adjust the water consistency depending on how thick or thin you like your dal. Add in the turmeric powder. Run a hand blender through the dal and smoothen it out. Alternatively, use a whisk or traditional manjeera or ravi to roughly blend out the dal to make it runny.

- Tip in the kokum with its juices, tomatoes, curry leaves, moringa pods and bring to a boil. Have a taste, adjust for salt, squeeze in the juice of half a lime and garnish with chopped coriander leaves.

- Tempering: In a tadka pan or any small saucepan, add in the oil and wait for it to warm up on the flame. Add in cumin seeds and lower the flame to avoid burning the spices and patiently wait for the cumin to start turning a beautiful deep brown colour. This is a crucial flavour profile for my mom’s dal, she will always brown the jeera deeply until it’s at the height of its aromatic abilities. Once you smell the intensity of the cumin seeds and see it turning deep brown, quickly add in the asafoetida and turn off the flame. Tip in the entire tadka into the dal and stir through. Allow the tempering to simmer in the dal a few minutes and merge with the rest of the ingredients before serving. Minimal though this tadka is, it places the flavour of the cumin seeds front and centre to be savoured as it should be.

- Serve with hot steamed rice and papad on the side. Maybe even twice fried potatoes or Sindhi aloo tukk, if you’re lucky.

1 Kowsalya R, Manoharan S. Health status of the Indian women-a brief report. MOJ Proteomics Bioinform. 2017;5(3):109-111. DOI: 10.15406/mojpb.2017.05.00162

2 Sanneving L, Trygg N, Saxena D, et al. Inequity in India: the case of maternal and reproductive health. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:19145.

3 Tzioumis E, Adair LS. Childhood dual burden of under– and over–nutrition in low– and middle–income countries: a critical review. Food Nutr Bull. 2014;35(2):230–243.