The Voice of Vasamalli: Origins, Roots, and Life in the Toda Landscape

“Listen to the air. You can hear it, feel it, smell it, taste it. Woniya wakan—the holy air—which renews all by its breath. Woniya, woniya wakan—spirit, life, breath, renewal—it means all that. Woniya—we sit together, don’t touch, but something is there; we feel it between us, as a presence. A good way to start thinking about nature, talk about it. Rather talk to it, talk to the rivers, to the lakes, to the winds as to our relatives.”

―

On a crisp November day circa 1960, a young Toda girl returned home early from school. Home was the ancient hamlet of Nerrguj or Nerrkasi mund, near Sandynallah in the Nilgiris (where she lived with her maternal grandparents), close to the only tribal school for girls in the area.

It was still bright, so she took the buffalo calves to graze the endless pastures and sat by her favourite tree—a rhododendron, and the very first tree she had climbed just a few weeks ago. She’d followed in her companion’s footsteps up the tree, but the mischievous boy—some three years her senior and uncle by way of familial ties—swiftly descended back to the ground in the blink of an eye. Left to her own devices, the terrified girl had to make the perilous descent by herself. But, she thought, smiling softly to herself, it had all worked out well after all—now she could climb any tree.

Anticipating untimely rain, she looked up at the spotless blue sky now being rapidly veiled by dense clouds. She usually waited it out until the rains abated and the herd had their fill of grazing, before heading home. Though this was a solitary ritual fraught with uncertainties of weather and wildlife, it was one that the girl deeply treasured. On that day, however, she needed to make haste so she could be home before the lunar eclipse set in. As she walked, she dug out some fresh tubers of kafehll(zh), a Shola plant (Ceropegia barnesii, now sadly very rare), which the kids and adults ate raw with gusto. The rowdy calves had to be led back into their pen. All this had to be accomplished, and grandmother helped with chores and the evening meal.

Only then could she and the other kids help save the Blackknaped* hare from the snake’s chase. As with many ancient cultures, the Todas too believe that there is a hare on the moon and that the lunar eclipse occurs when the snake swallows the moon. They pray and weep loudly to drive the snake away, waiting for the completion of the eclipse, so the hare is back to its original abode, the moon.

“Don’t let the snake catch the hare!” she muttered, her hands joined earnestly and her eyes affixed to the eclipsed moon captured in the reflection of a shallow brass bowl filled with water.

The tale goes that a dairy priest, the pollol and his assistant, the kwalktmok, went out to gather honey. The pollol chanced upon some honey in a tree cavity and, wanting to keep it to himself, did not disclose this discovery to his assistant. On the other hand, the assistant discovered another hive with very little honey but followed the sacrosanct rule of gathering the liquid and bringing it to the priest in a leaf cup. Because the pollol and kwalktmok were cousins, there was an additional ritual of seeking consent from one another to consume the sacred honey.

The next day, the pollol returned to the shola to retrieve the honey he had discovered in the tree cavity and collected into a bamboo container. Alas, the container detached from the sling, fell to the ground and broke open. The spilt honey turned into a snake that attacked the priest, who ran for his life. As he ran, he saw a hare and threw his black waistcloth on it, confusing the snake, which then chased the hare, assuming it to be the pollol. The hare looked to the sun for protection but it was the moon that came to its rescue. Meanwhile, the leftover honey from the pot continued to drip, become a stream and then took birth as one of the most sacred water systems of the Todas, the Mukurthi-Pykara river.

Stories and legends such as this might sound like fairly tales and superstitions to city dwellers like us but to the indigeneous people, they are stories of genesis–as real and layered as life itself. They are not just windows into the cultural soul of a place, they are also pathways into the landscapes. They provide insights into the local ecology that can, in turn, lead to preservation.**

And so, during each lunar eclipse, young Vasamalli continued to say her prayers and shed some tears to save the hare. Growing up in hamlets situated in the folds of ancient grasslands, hugged by the densest of forests, this was her favourite tale.

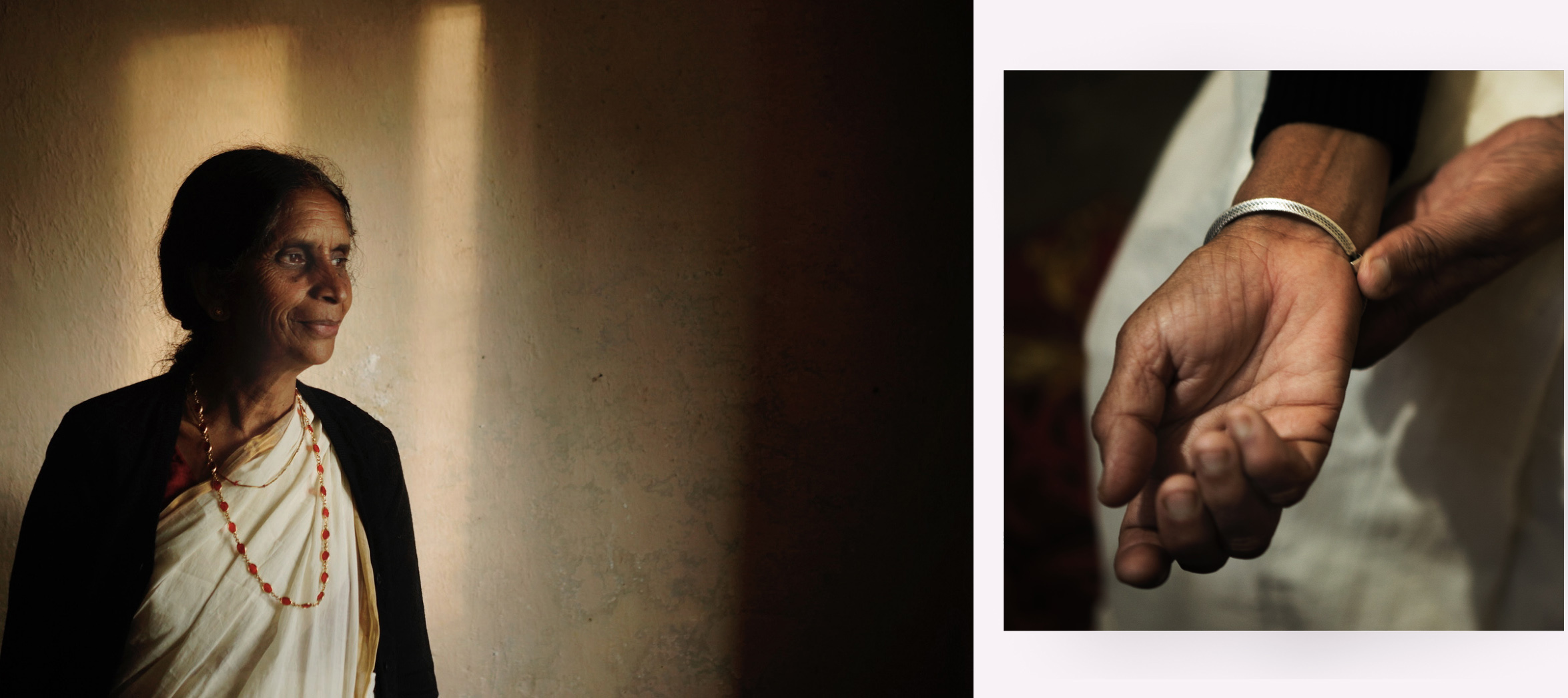

Vasamalli Kurtaz is the first woman to earn a postgraduate degree in the Toda community.

A foremost scholar from the community, she is a member of the District Tribal Welfare committee and was a member of the State Wildlife Board until 2021. Now in her sixties and spry, and no less spirited than the little Vasamalli who climbed trees, she continues to inspire all those who meet her, with her tireless community work and deep understanding of her land.

I had met her some years ago, and as we became better acquainted, sought her out to learn about the Nilgiris’ changing monsoon patterns. Her remarkable personal journey, her warmth, and her deep roots in this land drew me in. Vasamalli was in the process of compiling origin stories of the approximately fifty sacred mountain peaks of the Nilgiris.

The Todas have mountain-dwelling deities for every peak across the Nilgiris. These mountains are living ancestors protecting and guiding people on the path to the Amunodr, or the other world.

“If you ask me, Nilgiris is the place of our birth,” she said.

“We are from here. We did not come or migrate from anywhere else as has been sometimes suggested. Everything begins and ends here. The afterworld Amunodr is right here—clear, visible paths lead to this place. Many religions tell you that humans were once divine. I do not know whether this is true for them or not, but for the Todas, this is true. When we ceased to be divine, Taihkirshi ruled the mortal world or Immunodr and created the many clans and the sacred dairy while her father ruled the other world or Amunodr.”

Much of Toda life was (and is) centred around the dictums of their supreme deity, the goddess Taihkirshi. The Todas believe that Taihkirshi and her father Aihnn, are the supreme father-daughter duo who once ruled their pastoral community.

All of this was passed down orally through generations. How did Vasamalli learn so much? How did she manage to preserve so many stories and precious indigenous knowledge of her community in her safekeeping?

“I learnt by listening to and keenly absorbing what the elders said. By asking them many questions about our origins, culture, seasons and botanicals. I did not understand all of it then, but I can now. Stories and rituals are intertwined with the landscape and the people. So, everything is meaningful; one should understand that.” She said.

That struck me as profound. Had I ever held the stories I was told with such a sense of reverence and deep attunement? We were never inclined to listen the way indigenous people have done for centuries. Our languages provide for a method of recording that does not require the kind of intuitive processing, powerful imagination and deep knowing that oral linguistic traditions do. “Even the skin has a role to play in the act of listening,” a Kurumba elder once told me.

I wanted to hear Vasamalli’s retelling of some of these stories just as she had heard them from her elders, growing up. Every time we met, I have had the good fortune to listen to an old Toda tale or two, interspersed with her own life stories.

She visited me one afternoon for lunch after volunteering at a health camp near Kotagiri. She’d spent three days roughing it out with barely a full night’s sleep but was no less enthusiastic about picking up on our conversations. Over lunch, we found ourselves in a fascinating discussion about how she’d publish her stories. To fully capture the soul of these tales and the cultural cohesion they provided, I’d been encouraging her to record them in the Toda language through voice and gestures in the native storytelling tradition, alongside the writing she was doing in Tamilzh and English.

The Toda language is Proto-Dravidian with whispers of today’s Tamilzh. Made up of many fricatives (consonants pronounced with the friction of air) and trills (vibratory sounds), the language is rich with unusual phonetics, which makes oral storytelling all the more vibrant.**

Vasamalli’s storytelling style is both gentle, and pantomime and I love listening to her bring the Toda lore alive.

“Oh, Ramya! It just so happens there’s a lunar eclipse today! Do you remember the hare and snake story I told you?” She exclaimed.

“Shall I tell it again? You can record it this time.” And so I did.

“What is the Toda language called?” I asked her later that day.

“It’s called Awlwoll, which simply translates to man or human being. So I suppose you could say it is the language of man?” She said, thoughtful.

To me, the language of man sounded like a primeval language of genesis and wisdom. One that reached the deepest of roots that connected man to the vast, coexisting networks of sentient beings.

In Vasamalli’s world, language was a tool for expression and storytelling that went beyond the use of words. It defined the subtle contours of a culture, identity and belonging. Such languages presented diverse, inclusive ways of seeing, where extensive knowledge and stories were captured beautifully in myth, ritual and memory. These were both personal and collective, extending well beyond personal experience and representing a shared reality.

Though hopeful, she wasn’t sure if the younger Todas would process the ancestral knowledge in the same way that her generation still did.

“Nowadays, there are calendars.” She said.

“We didn’t have them, but we could predict everything—seasons, eclipses, etc. It was all learning from nature—you must listen and live deeply to learn from nature.”

It occurred to me that the aspect of listening featured heavily in our conversations. The kind of knowledge coded into languages with more listening than speaking, undoubtedly holds the key to addressing the crises we face today. With indigenous languages like this already becoming endangered, we run the risk of losing both experience and regenerative imagination in our responses to the climate and ecological crises we are fraught with.

How can we create a platform for the knowledge and experiences of minority and endangered language holders so that their words and wisdom reach new audiences? I asked her about this.

“My education was wholesome,” she said thoughtfully. “I had the best of both: I learned from the elders alongside my mainstream syllabus, which included traditional knowledge too. See, we had no lights, and we had nothing much else to do late evenings but listen to the stories the elders told us. My grandchildren, who are entirely mainstream educated, don’t seem very inclined to hear these stories. Not yet, at least.”

“We just have to keep trying to reach these to them, though. In fact, it is necessary that we do. With opportunities and technology now available, we should document these stories and Traditional Indigenous Knowledge in ways palatable to this generation. Or else all this will be lost not long after me. We could, for instance, record all the stories vocally in our language as you suggest, and in Tamizh and English too, perhaps.”

We finished our lunch and settled on the couch when she noticed a beautiful throw adorned with Toda embroidery. It was a birthday gift I’d received from a dear Toda friend, Seeta.

“All traditional motifs.” She said.

I then told her about a project I had been working on, which involved casting the stunning Toda art in a new light. A small group of Toda women artisans and I were exploring possibilities of working with better, newer fabrics, moving away from the typical coarse cotton they were used to.

The Toda women embroider abstract, nature-inspired motifs into red and black geometrical designs on the cotton cloth, which allows the threads to be counted easily. No embroidery frame is used, and the women count the threads with their fingers. Thread-counting forms the basis for executing a specific design with the appropriate stitches. The cloth, needles, and the black and red cotton yarn they now use are locally procured.**

“Did you know that the needles were made of twigs from a specific Shola plant at one time? And the cotton too was woven locally. Plant fibres perhaps—I’m not too sure. Cloth was extremely scarce, you see. It was precious—even as recent as some decades ago.

“I’d describe the Toda embroidery more as an ethnic art with no commercial significance in those days. I mean, we didn’t need any of our ways to become economic practices. You see, we did not need money––why would we when everything we needed was abundantly available from our land and forests? Eventually, ghee became the product that was exchanged for goods, and the embroidery coming into the economic mainstay is very, very recent.”

Now GI tagged, thanks to the concerted campaign by the Toda Nalvazhvu Sangam, Keystone Foundation, and the Toda community itself, the Toda embroidery is perhaps the only enterprise from the community which has received its due recognition the world over. Sadly, only a few hundred artisans from a community of no more than 1700 people practice it making it an art form that needs thoughtful and continued preservation.

It was almost 5pm when we reached her hamlet of Kaarshmund near Ooty. I walked with her to her warm home, which so cleverly emulates the traditional wild rattan and thatched barrel vaulted Toda homes but with sustainable modern materials.

Inside, between the kitchen and the living area, was a neat line of family photos. She pointed to a portrait of a handsome bearded man–her husband, Pothili Goodn.

“He was a revolutionary man.” She said.

“He was a thinker who encouraged me to pursue a career—I worked at Hindustan Photo Films for 15 years, even with young children. He did so much good for the community and was instrumental in helping stop the buffalo sacrifice that was still prevalent in the community.” She adored him, I could tell.

“My grief at his passing is impossible to describe. He is so missed.” She said, making some tea for us.

“Why don’t you take a walk to the temple?” She asked after we finished tea.

When I returned from my walk, she was chatting animatedly with her two granddaughters. The girls posed for a photo with their grandmother upon her insistence.

“So will you take some pictures for me? For my book on the stories of sacred peaks of Todas,” she asked.

“If it is not too much trouble.…”

“It would be my privilege,” I said, and hugged her before getting into my car.

“They are not just mountains, you know.”

She said, when I rolled the window down for a final goodbye.

________

* The Toda Landscape: Explorations in Cultural Ecology by Tarun Chhabra, Chapter 9, Sacred Waters

** Soul of the Nilgiris: A Journey through the Mountains, Ramya Reddy, excerpts taken from pages 54, 92, 97

Such a beautiful endeavour …. To know the Nilgiris , and it ‘s people , history , and traditions

Thank you so much!

We recorded Vasamalli in 1984, when she orally translated lyrics for songs being sung by Toda women. She might remember me and my late husband, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy. The recordings are being posted by the UCLA Digital Library on May 22, 2024. A zoom link will be provided. https://schoolofmusic.ucla.edu/event/repatriations-restudies-and-repercussions-the-bake-jairazbhoy-digital-archive-of-south-asian-traditional-music-and-arts/

Professor (adjunct) Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy Ph.D.

acatlin@ucla.edu

Hi Professor Amy,

Thank you for your warm appreciation and for your sharing. Vasamalli can be contacted via her phone number. If you can drop me a message at ramya@coonoorandco.com, I’d be happy to share it with you.

Warm regards,

ramya

We recorded Vasamalli in 1984, when she orally translated lyrics for songs being sung by Toda women. She might remember me and my late husband, Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy. The recordings are being posted by the UCLA Digital Library on May 22, 2024. A zoom link will be provided. You are invited to attend the launch: https://schoolofmusic.ucla.edu/event/repatriations-restudies-and-repercussions-the-bake-jairazbhoy-digital-archive-of-south-asian-traditional-music-and-arts/

Many thanks for you beautiful work! How can we contact Vasamalli?

Yours,

Professor (adjunct) Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy Ph.D.

acatlin@ucla.edu