Pathways into Kinship: Lessons on Belonging from the Monarch Butterfly

Listen to this story. Narrated by Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder

It was only after the last box was unpacked (apart from ten or so boxes we quietly crammed into a closet and planned to forget about) that I realized—with some consternation—that our family’s recent move was still very much in progress. Only after the mammoth, months-long physical effort of packing, donating, cleaning, departing one home and then…transplanting, arriving in a new place, and unpacking, did I remember, from previous moves, what was still to come. The emotional work. The bodily, sensory work. The thousand and one tiny steps that would be required to truly arrive: to move from the unfamiliar into the familiar.

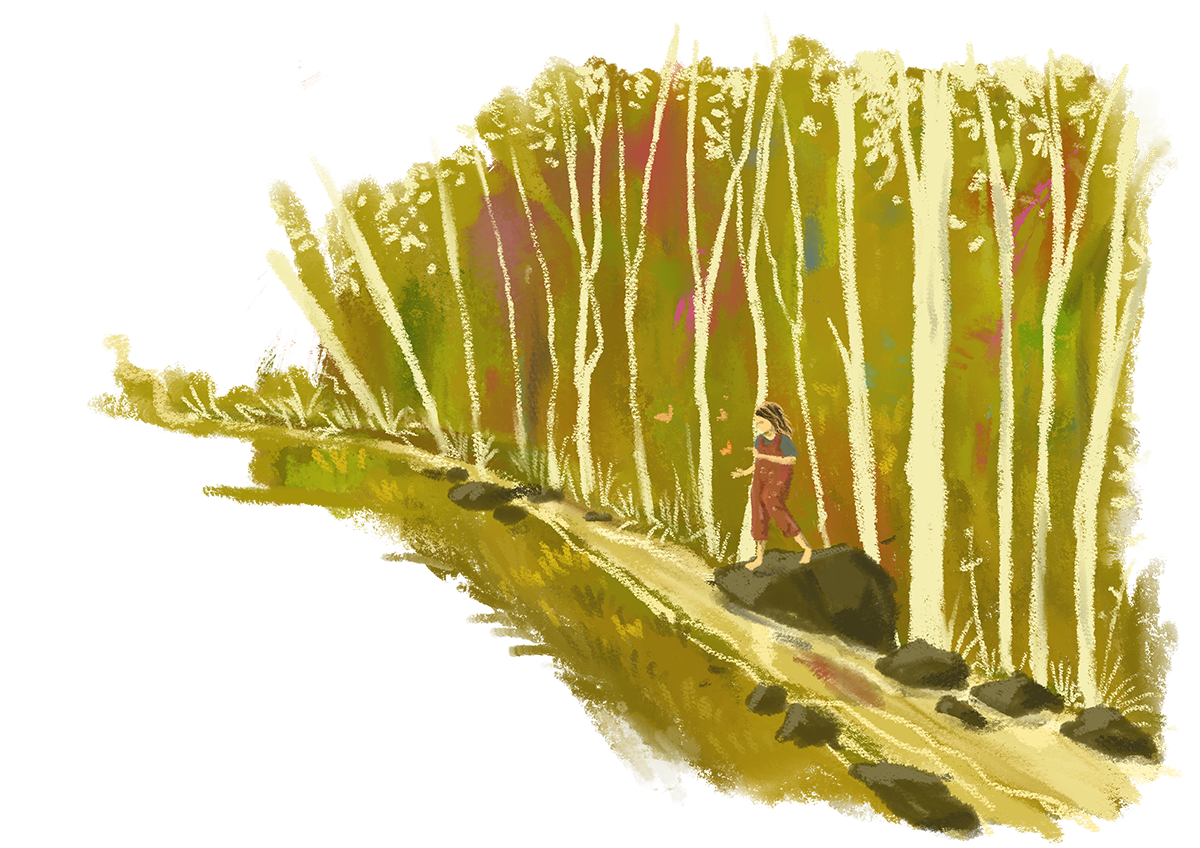

The thousand and one tiny steps that would be required to truly arrive: to move from the unfamiliar into the familiar. The countless times I would orient, then orient again. Navigating pathways into the different flavours of each season, the different streets, different faces, wending through all of the new configurations of home. How long, I wondered, would it take to feel we belonged?

This summer, my family and I moved from Maine to Vermont. While this decision fulfilled a long-held dream to live in a rural community surrounded by open space, bringing that dream into reality was as exciting as it was painful and deeply uncomfortable. All that we had carefully constructed within our imaginations suddenly gave way to the distinct contours and patterns of reality—new ways of doing and being, expected and unexpected challenges, and all of the complexities and dimensions that only come into focus when one is living and breathing what had previously been safely housed as abstract thought.

There’s a small brook that runs alongside our new home. It comes down from the mountains and splashes and wends its way over rocks and boulders that have been worn and rounded by this constant movement of water. In the first few weeks of living here, we didn’t know the brook’s name. It is squiggled across several local maps but with no accompanying words to identify it. It didn’t show up in any Google searches. Finally, one of our neighbours told us it was called “Brook Street Brook,” named after the street we now live on.

Our four-year-old daughter seemed to share our view that this was neither a satisfying nor compelling name, and thus decided to name the brook herself, after the creatures she always sees fluttering and flitting about when we climb down to sit by the running water. She calls it Butterfly Brook.

The monarch, Vermont’s state butterfly, is a migratory insect with wings that evoke velvet sunset and soft fuzz of ripe peach, outlined in bold black strokes interspersed with specks of white. A portion of the monarch’s eastern North American population summers here in Vermont and winters 3,000 miles away in central Mexico.1 It is astonishing enough that this tiny, elegant creature makes a journey this epic twice a year, the only butterfly known to do so.2 But more astonishing still is this: while the journey south is undertaken by one generation, the journey north unfolds over as many as five generations.3

The monarchs will take leave of the oyamel fir trees in Mexico, fly a few hundred miles north, find a patch of milkweed where they then mate and lay their eggs. The eggs hatch into caterpillars which feed on the milkweed, form a chrysalis, and emerge as butterflies into a place they have never been before. This generation continues the journey, only to repeat the process, bequeathing the remaining path ahead to the next generation.4

And yet, the monarchs know the way. Somehow, the pathways they navigate, though never before physically traveled, guide them reliably home. The earth’s magnetic pull and the position of the sun are believed to play a role, but it largely remains a mystery to human understanding how this migration is possible. It is, it seems, an inheritance of collective knowledge, an innate sense of direction, and the ability to effortlessly belong somewhere entirely new.

*

I’ve moved many times in my life, and I’ve wrestled with what it means to have chosen not to live in the place of my birth, the place of my upbringing, or the place where my ancestors lived. Have I abandoned some place-based inheritance, some innate sense of direction? As someone who believes that the climate crisis is, at heart, a spiritual crisis whose cure requires coming back into a deep relationship with the living world, I worry that I have uprooted too often. Now, as a mother, I wonder how to help my daughter build a sustained and reciprocal relationship to a home place. I long to bequeath her with an effortless belonging. I want to put down roots in a place where she can grow up with a sustained connection to a particular ecological community.

The monarchs that we saw this summer from Butterfly Brook have helped me clarify my questions. Are there deep ties and connections that we carry within us, no matter where we are? Which connections to the earth are innate and which are forged through time and attention in a place?

Now, as summer turns to fall, the resident monarchs of Vermont are preparing to journey south for the winter. But these insects are now journeying through increasingly wounded landscapes and into an uncertain future. The monarch population is declining in both eastern and western North America due to habitat loss and fragmentation, pesticides, and the effects of climate change.5

There is a lesson here, too: pathways into kinship move in multiple directions. They are reciprocal. It is not enough to simply make a home for ourselves, to focus on our own belonging.

Home is not a silo. Arriving into the familiar means recognizing that we are interconnected to the living world around us, and means learning who and what those connections touch. The deeply ingrained pathways of and into relationships that we carry within us, no matter where we are, ask something of us: to locate our belonging within the belonging of others. The monarch is not simply a metaphor, a way of thinking about home, it is a living part of our home, and we are part of the butterfly’s home.

In late summer, we collected milkweed seeds from a nearby field, dried them on the windowsill, and carefully placed them into a paper envelope. In the spring, we’ll plant a butterfly garden alongside Butterfly Brook. As the snow melts and the ice in the brook thaws next spring, we’ll keep watch for the arrival of the monarchs and know that our own, ongoing arrival into this place is underway.