The Old Dog in the Kitchen

Listen to this story. Narrated by Smriti Rana.

1989

It is dusk on a Friday. We get into the old Standard Ten Companion – a car that draws looks of amusement not just for its faded vintage but also because every local knows that 4 out of 7 times, it needs passers-by to push it down a slope to coax its engine to sputter to life. Ooty is small enough to recognize locals by the cars they drive. Once it coughs and starts, we drive to Video Links in Upper Bazaar. It is a six-foot by twelve-foot cubbyhole of a store stacked with video cassette tapes, titles carefully handwritten on white labels. It’s the only treasure house of Hollywood movies in town.

Outside, the air is infused with the smell of chilly bajjis frying, and sweet milky tea is being poured into steel tumblers on a crisp, cold evening.

Mamma encourages me to choose something other than ‘Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’ or ‘The Gnome Mobile’ which I have already rented three times this year. “We may as well buy the tapes.” (Eyeroll) I try to expand my horizons and pick a new one.

This is a weekly treat.

Walking home from school, the sole of my “Naughty Boy” school shoes comes off from too much boisterous play on tarmac. This sleepy hill station is not yet overrun by consumerism. The internet and online shopping are not even in our consciousness. If something breaks, we don’t discard; we repair. We walk down the hill to the St. Stephens Church intersection. The old cobbler is reliably in his usual corner. He fixes my shoe with not-so-subtle stitches.

Once a fortnight, we eat out. Choices are limited and we know exactly where we will end up. Shinkows. We pretend to study the menu. But we already know what we are going to eat. Numbers 5, 13A, 62 and 83. Mr. Powks comes by to ask if everything is in order. Mamma reminds me of my manners. I look up from my meal and shyly say hello. He has kind eyes that twinkle as he smiles.

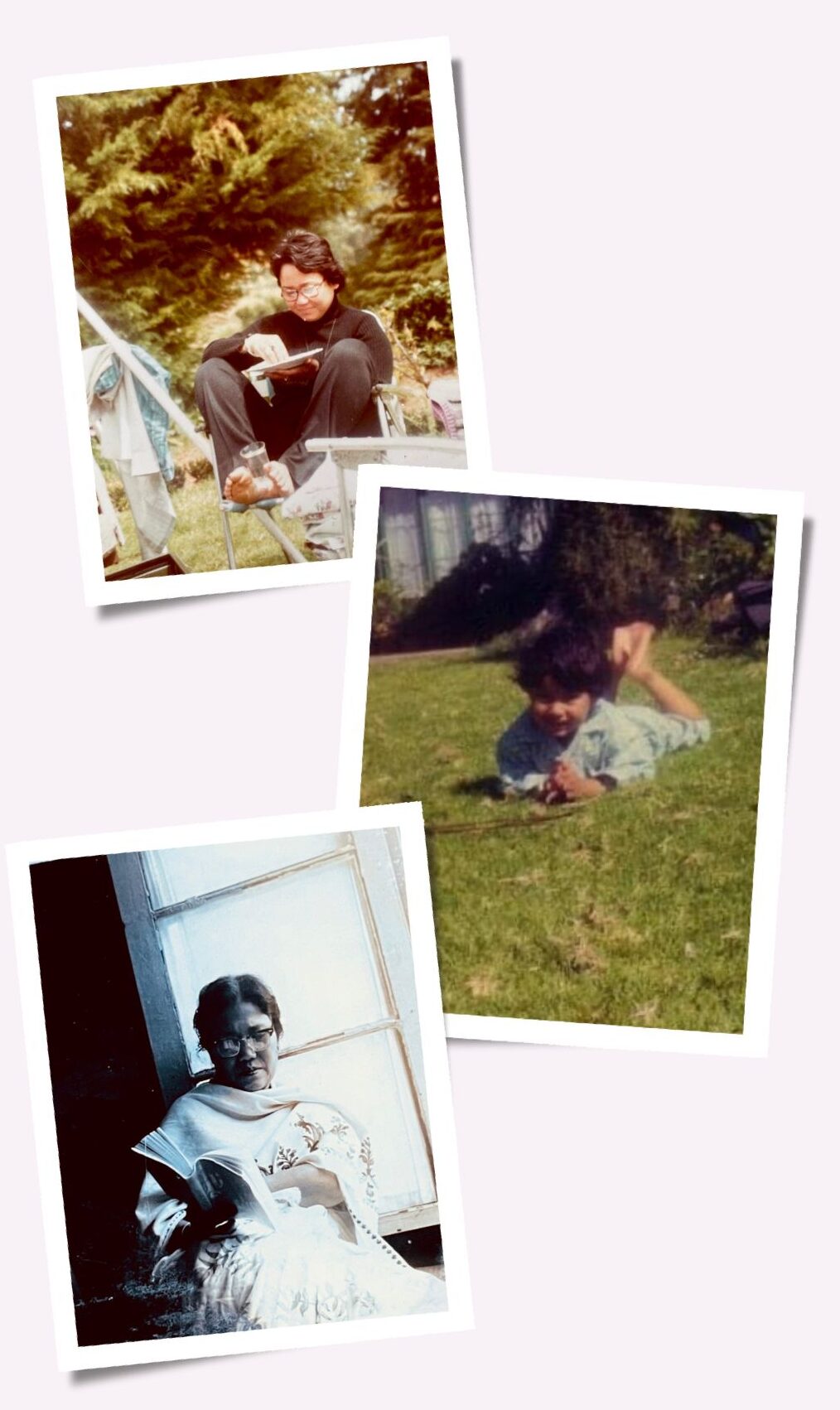

Every other meal, though, is lovingly cooked by the two master chefs who rule the kitchen of my childhood home: Mamma and Muaji, my grandmother. Our bookshelves hold recipe books from around the world, interspersed with Agatha Christie novels. Mamma is a voracious reader and likes to read as the food simmers on the 4-burner Aga stove or something bakes in the oven below. This Aga makes noises that would frighten me when I was younger. Now, it just seems like a gargantuan, grumpy, but good-natured relic peculiar to our kitchen, not seen at any of my friends’ homes.

The big window of the kitchen looks out into a wooded grove that holds many secrets. I know all of them. I know this cluster of trees and everything between them by heart. I visit it everyday, accompanied by my dog. Muaji hands me a snack to take along. On weekends, we spend hours exploring, looking into hollows, asking who lives there, stashing treasures under roots and gathering pine cones for our magic rituals. There is a spot under an elder tree with magnificent roots that I like to sit and read in. The dappled sunlight makes galaxies on the forest floor.

Mamma looks out from the kitchen from time to time. Her face bears no trace of apprehension. I am safe where I am.

We have a lush garden, carefully tended by our faithful Giriyabhai. A man of few words and green thumbs, under whose careful touch the garden bursts into bloom every season. I sit with him as he tills the flowerbeds. He answers every inane question I ask with a story. Why is he planting these flowers here and not there? How does a plant decide what colour a flower would be? Will butterflies come for this one?

I never ask what they are called, and he doesn’t bother to tell me. And anyway, who needs a name when you can identify a plant by scent and story?

Mamma is a champion golfer. She is celebrated on and off the course. This is another place I know by heart. I have walked every inch of it with her. It is here that I ask her questions about God, prompted by scripture classes in the Christian school I attend. I am confused by my teachers insisting that there is only one path to heaven. Muaji sprinkles water from the Ganga on me every morning as I head to school. To afford me the protection of the three hundred and thirty million gods and goddesses of the Hindu Pantheon. “Don’t let anyone tell you what to believe,” Mamma says, “Not even me. But remember, someone who believes in a higher intelligence may have to explain the existence of sadness and pain. But someone who doesn’t, has to explain the existence of everything else.”

It will be years before I understand what she means.

Evenings find the television on, the two ladies taking turns to chop and stir the day’s offering. Whatever emerges from that kitchen is eaten punctuated with conversation about the day – mostly mine. We discuss my homework and classroom goings-on, peppered with curiosity, affectionate jibes and validation.

The children of our family are initiated into eating chillies very early, and no meal is complete without “Khursaani” or my favourite “Bombay duck bharta” made from equal parts dry bombil and red chillies. On days my mother is feeling more continental we have pork chops with caramelized vegetables and mashed potatoes infused with a flavour I don’t taste in mashed potatoes anywhere else. I don’t dwell on this difference. I only know this is what the mash tastes like in my home. The TV is turned off. The last of the embers in the fireplace whisper. Wisps of woodsmoke settle in my hair.

On days I feel unwell, I am fed a special mutton stew. My bathwater is infused with eucalyptus oil. A couple of drops are sprinkled on my pillow to clear my stuffy head as I sleep. I dream of eucalyptus trees.

2024

There is a break in an unusual monsoon. The wind has blown with furious and volatile velocity, knocking over trees across the district. Power has just about been restored and I need fresh groceries. It has been a stormy year. I struggle to find my bearings. Ghosts appear in unexpected places.

I must finish my errands, grab lunch and head down the hill to the jungle home I now inhabit. I must do this before it grows too dark or the storm picks up again.

My car purrs to life with a single push of a button. The popularity of this model and colour ensures my anonymity. I am invisible.

It has been a year since the last elder in my family died. It has been two decades since everyone that lived in that home with the garden full of stories has died. There are no witnesses. There is no one to corroborate remembrance. Orphanhood has rendered my memory unreliable.

I am now a master jigsaw puzzle assembler: I piece together my genealogy with stray slivers of stories – some gleaned from memory, some deduced from old letters, some guessed at from clues in photographs. I try to excavate the minds of people who might know something. Anything.

I am a keeper of histories.

I am discovering much of it is mythology.

Grief stirs its head like an old dog. Sniffs the air. I scratch behind its ear and gently will it to sleep. It curls up beside me. Loyal.

This dog is now a constant companion. We go into the woods together everyday.

I look at my grocery list. Lettuce, spinach, zucchini. An old memory settles unbidden on my tongue and instinctively leads me to a very specific part of the market. To get there, I must navigate the Upper Bazaar. The recent rain has washed away all traffic sense and I am stuck in a snarl. I scan my surroundings. I am right in front of Video Links. The sign is faded, and the crowded shelves of this tiny store now house an unremarkable mix of household goods. Who even owns a VCR anymore, I wonder as I briefly entertain the idea of asking the man at the counter what he did with all the Audrey Hepburn films, or the “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” and “The Gnome Mobile” tapes. We SHOULD have bought them. (Eyeroll). A horn blares behind me.

I park and walk to the section of the market that sells dried bombil. I have called it “Bombay Duck” all my life. But the shopkeeper doesn’t know it by this name. I pull up an image on my phone to show him. A story accompanies the image. I know this story. Bombil is considered a “strange”’ fish and gets its name from the train that carried the sun-dried delicacy from Bombay to the Northeast of India. The Bombay Mail, or the Bombay Dak – a postal train. A trans- subcontinental journey transported this curious ingredient from the West coast of India to where my grandmother grew up in Tripura. It is not indigenous to the region, and definitely an acquired taste. Acquired and now beloved 3000 kilometres away from its origins – the magic ingredient in so many favourite dishes.

I buy half a kilogram, knowing full well that it’s too much. But it brings Muaji back to me.

It’s almost too late for lunch, but if I hurry, I can make the last order at Shinkows. The waiter knows what I will order and doesn’t bother with the menu. “5, 13A and 62?” he asks. Yes, I nod. 83 was discontinued around the time I went away to college. I miss it. I eat alone. But not quite alone. Quiet echoes from four decades past mingle with the white noise of other diners.

I ask the waiter about Mr. Powks. He is in the kitchen. I pop my head in and say hello. He twinkles a smile back at me.

I drive past the cobbler on my way out, his little shack now a little smarter, with a new signboard emblazoned over it. “Shoe Doctor,” it says. A younger man now sits in it, with two other men clearly there just for a chat. The three of them share a cigarette. Business is slow. Hardly anyone repairs broken shoes these days.

The light is beginning to fade. A man walks past my line of sight wearing a monkey cap and tweed jacket – the signature style of older, working class men in these hills. For a moment the shadow falls on him sideways and I see Giriyabhai. I now know not just the common names of flowering plants, but also their scientific ones. All this knowledge, but I don’t truly know them without their stories. What if I went up to this man and asked him if he did?

I take the road I always take, the one that hugs the golf course. The light through the eucalyptus trees is almost blue. The silhouette of the hills in the distance are as familiar to me as the smell of the trees. I roll down the windows and breathe in. I have had to explain pain and death many times in the last two decades. I remind myself of the exquisite beauty of everything else.

I’m home. I’m hungry. I walk up to my terrace garden to pick out the ingredients I need. I walk past the Basil, the Chamomile, the Sage and the Roses to the Khurasaani corner. The Birds-eye grows beside the Bhoot Jolokia. They look deceptively tame. The Enam patta thrives in a trough I have protected for over a decade. One of the more lasting gifts from my mother, brought from Tripura. This year, the rainfall in this part of the world must have been closer to what this plant is used to back home, and it shows. I learnt its English name: Fishmint, soon after my grandmother died, so I couldn’t tell her. I hold close this information that doesn’t interest anyone else one bit. On a shelf in the kitchen are jars of fermented bamboo shoot from Asan bazaar in Kathmandu, next to a box full of Timmur seeds. In the shelf below is a bottle of Kasundi mustard. A lightbulb goes off in my head. Of course! This is the secret ingredient in the mashed potatoes!

On days when the old dog is overly demanding and sits especially close, I cook using a weathered claypot from Nepal, over an outdoor woodfire stove. Traces of people I have loved linger in woodsmoke. The meal that emerges traces the cartography of my ancestors. Myriad ingredients come together to converge here where I stand, in the shadow of the Blue Mountains, 3000 kilometres from infinity.

In the half-light between memory and moment, you’ve caught something.

I felt as though I am walking with you in the market, the golf course, in your terrace garden.

Heartwarming story and beautifully narrated. ❤️🩹

Your writing is exceptional. I was transported to another time…when things were simple. It sparked the memories of the years I spent in Ooty, I could smell the eucalyptus trees and feel what you felt. Really moved by your story