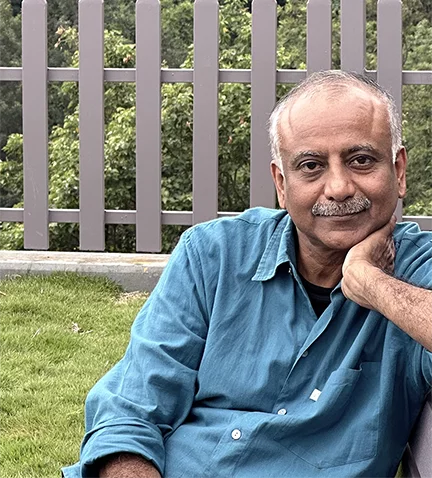

WORDS BYPrabhu Viswanathan

PHOTOGRAPHY BYRamya Reddy

Listen to this story. Narrated by Prabhu Viswanathan.

Art washes from the soul the dust of everyday life

~ Pablo Picasso

The eleven year old boy, dripping all over his trail, laughing uproariously as he barrels through the rain, isn’t Pablo, nor is he even an artist.

His name is Adam, and he lives in a refugee settlement high in the Blue mountains. He loves water. It’s been pouring madly this week, soaking brave bushes and imperturbable trees, pelting cowering rooftops, slip-sliding across village streets and rough country lanes, reborn again and yet again as chirpy little streams that giggle and gurgle along the uneven stone pathways just like here and now, kissing the steps of my studio and pausing for air.

Moments ago, Adam was beside himself with unbridled joy, but he is usually a taciturn child. For him, the sifting sands of time and the ticking of clocks have no meaning. His days move into nights, as an irrepressible sun journeys across a mountain sky, setting softly against a shape shifting and rising moon that gently casts the shadow of troubled sleep upon his sad eyes.

He came to me three weeks ago, a frighteningly numb and very silent boy. I smiled at him tentatively only to be answered by a scared look that owned an unending pain, that indisputably mirrored his savaged, dark mind.

I learnt later that Adam’s family spent days and nights upon a smuggler’s boat escaping the War, making their way from Talaimannar in Mannar at the North end of Sri Lanka to the tip of Southern India heading inexorably towards Rameshwaram, before equally inevitably being abandoned on a sand dune near Dhanushkodi, rescued barely alive by the Coast Guard and deposited unceremoniously into a distorted camp that sits like an itchy rash on the beautiful slopes of the Nilgiris. My home!

I am an art therapist. I work on the human canvas.

I create an environment to make you safe and comfortable, and to give you my ear and heart.

On the first day, I give Adam a sheet of paper and a pencil. He crushes the paper into meaningless pulp and sucks the pencil raw in an ominous, quiet rage. As days pass by, the paper becomes tidier and the pencil lasts more than one session. They transform into canvas and brush – means to lend words to his trapped inner voice.

Three weeks later, he is obsessed.

I have upgraded his tools to include a pallette and colours. He draws from distant memories of school days, stick figures of friends long vanished, his once buoyant fishing village now mere lines in the sand. He paints the yellow two storied home that he lived in, with its dulled red tile roof and he recalls the small pond filled with nelum.

But once in a while, his predictable brush turns berserk, the raw tip flattening the bristles as it screeches along the suffering paper that splits and tears into pieces,,as he weeps uncontrollably till his stormy breath turns soft and sleepy. At these moments I leave him alone as he desperately searches for a tremulous, temporary peace of sorts.

As a therapist, this is my goal- to painstakingly draw out a sadness he cannot comprehend from within a life he cannot fathom.

By enabling Adam to express his distress with the tools of my trade, I learn about his past, his suffering, the roots of his endless pain, the recurring nightmares of escaping an exploding IED upon the beach they were pushed off from, shouts and screams and gunshots as the soldiers trampled upon sand and flesh.

My room is a sanctuary without rules, and here he spews out his innermost traumas.

Adam loves the colour Blue.

In the midst of the rain that he loves so much, today is a good day. He is happier than he has been for a while, eager to converse with his emotions laid out by his own hand as lines and space and form.

He calls me loku amma.

He is healing.

It is important that Adam feels safe. He needs to accept, and be at home in his environment, know that the chair he sits on is not rocking in a rickety boat to nowhere, and that his brush cannot be snatched away from him like a friend on the beach, and that the water on the table is for him to drink from, not to drown in. He is an aftershock of a cataclysmic event, and is prone to display poignantly cringing reactions to anything out of a calm and complete ordinary.

In the early days, when he was able to hold a pencil, when his uncontrolled shivering grew into mediocre trembling and then consistently steady hands, I presented him with a whole toolkit-bundles of canvas, acres of clay, oceans of colour, warm wood and water, pencils, papers and fine brushes and now he is particularly fascinated by the soft and sticky clay.

He thrusts his hands and fingers and mind and heart into the medium, and his face lights up in ecstasy. He likes to knead and mould and make shapeless forms, covering his arms and hands with different textures and colours and layers, the cold clay warming the cockles of his very being, a clammy, soft security blanket. He tells me “loku amma,I want to stay like this forever”.

He likes to muck about in a table tub of warm water.

The ripples and little waves that form when he plunges his hands and shakes his arms and splashes the liquid all over the table and the floor and his clothes and his loku amma, make him dance madly. This playful violence is calming, allowing his uncurated movements to sing along with inner emotional beats, like a conductor newly discovering his ensemble. His brain slow dances to a gentler tune, his thoughts are sweeter.

No matter what the cause of disability or trauma, the goal of art therapy is to ‘ground’ the patients- guide them in their quest for peace, to shut their eyes and listen, or close their ears and look, and be aware of the safe, physical space. This soothes their senses, and allows them for the first time in a long time, to explore within themselves, recalibrate their abused minds and bodies with the help of external stimuli.

The wonder of art therapy is its ability to tell complex stories, to reveal hitherto unrevealed emotions, to draw out negativity and to heal with its simple tools of water, clay, toys,brushes and a blank canvas.

To many suffering individuals, especially children, art therapy is more than a tool to express themselves, it is a potent path to healing and being normal again. Each client is different. A child may have a learning disability, another is autistic or dyslexic, some children have ADHD or PTSD, some are refugees, abused, ignored,shamed, and there is no single way to heal.

Outside, the rain has softened to a drizzle.

I ponder the reasons I moved to the Nilgiris, to practise this healing art, to try to help those who are unable to help themselves. The blue mountains are the ultimate therapy to me, my own medicinal riches.

After Adam has skipped away into a wet world, I follow his path. It is a cool, inviting night. As I sip my tea, I look up into the black sky and listen to the sounds of the night.

Adam is better today.

He is dancing once more in his beloved rain that washes the dust off his soul, making him feel whole again, at least for today.

One day, he will be free!