WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BYAhtushi Deshpande

For years, the Himalayas have been both my refuge and sanctuary. In these untouched landscapes—where silence speaks and the natural world hums with primal energy—I’ve felt a deep resonance with the Earth’s rhythms. That pull—so visceral, so insistent—has called me back ever since I first set foot in the mountains as a teenager. It was no surprise, then, when the trans-Himalayan region of Ladakh began to whisper its lesser-known secrets to me. As I wandered its vast, untamed spaces and stumbled upon ancient rock engravings, the connection I had always felt with nature deepened—shifting from quiet reverence to a profound understanding. An awakening—that continues to echo within me and quietly grows to this day.

Ladakh, with its vast, uninhabited landscapes and stunning vistas, had captivated me since my first visit 20 years ago. In 2011—my fifth time in Ladakh—the region’s rugged beauty held an entirely different pull, one that seemed to hum with ancient energy, a force I hadn’t noticed before. Lost in plain sight, embedded in the very fabric of the land—its stratified rock—lay a collection of prehistoric imprints known as petroglyphs. These engravings, created with stone tools, turned out to be the only visible remnants of prehistoric human presence in the area. In the same way that nature utilizes accretion and erosion to craft the landscape into a magnificent artistic spectacle, our ancestors chiselled, pecked, and engraved into these very rocks, liberating forms captive within the recesses of their minds.

My journey to these stones began as an intellectual pursuit, sparked by my anthropologist friend Viraf Mehta, who first introduced me to the world of rock art. What began as curiosity soon unfolded into a deeper exploration—one that would shape my work and transform both my understanding of the land and my connection with it. When I first saw a rock gallery by the Indus River, nearly consumed by the landscape, I was struck by how the art was rooted in its origin, lying in situ. The site was Kawathang, in the remote Changthang area of Eastern Ladakh. A smattering of carved rocks was spread across a riverside flat, some dangling precariously, almost falling into the Indus River. The thought that I was standing in the very place where ancient artists had made these carvings thousands of years ago sent a shiver down my spine. Delicate hand engravings at the head of the site seemed to mark ownership of the land, their weathered edges and darkened patina whispering of a time and people long forgotten. The connection was immediate, and I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was witnessing something far more profound than I had imagined.

My journey to these stones began as an intellectual pursuit, sparked by my anthropologist friend Viraf Mehta, who first introduced me to the world of rock art. What began as curiosity soon unfolded into a deeper exploration—one that would shape my work and transform both my understanding of the land and my connection with it. When I first saw a rock gallery by the Indus River, nearly consumed by the landscape, I was struck by how the art was rooted in its origin, lying in situ. The site was Kawathang, in the remote Changthang area of Eastern Ladakh. A smattering of carved rocks was spread across a riverside flat, some dangling precariously, almost falling into the Indus River. The thought that I was standing in the very place where ancient artists had made these carvings thousands of years ago sent a shiver down my spine. Delicate hand engravings at the head of the site seemed to mark ownership of the land, their weathered edges and darkened patina whispering of a time and people long forgotten. The connection was immediate, and I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was witnessing something far more profound than I had imagined.

Little did I know that a single encounter would spark a decade-long field project. Traversing Ladakh’s vast desert became a journey like no other—enriched by the warmth and generosity of its people, who welcomed me into their homes in the remotest corners. In my desire to represent Ladakh in its entirety, I travelled across its high passes, secluded valleys, and riverine paths—from the icy heights of Saser La Pass (5,411 meters), gateway to Central Asia, to the remote wilderness of Changthang in the east. I traced the 400-kilometre course of the Indus, trekked for days, navigated rugged tracks, rafted down the Zanskar, and even flew over the ranges. No season was left unexplored. It felt like moving through layers of time—between ancient echoes and the pulse of the present—with each stretch revealing a history older than memory.

Scattered across the region, these engravings were not just remnants of the past but echoes of a time when nature and human life were inseparable. The recurring depictions of animals—ibex, yak, wild sheep, and snow leopards—reflect both survival and symbolic meaning. As the anthropologist Lars R. Aas notes, animals depicted in rock art weren’t necessarily chosen because they were hunted, but because they were “good to think with.” These creatures were not just food sources, but thought-objects—symbols of belief, identity, and a deeper cosmological connection. These markings speak to a worldview that deeply honoured nature—a wisdom we urgently need to reclaim. More than records of history, the stones also carry a timeless philosophy of coexistence.

The imagination soars in trying to derive meaning from the petroglyphs. Was this sacred art—expressions of spiritual beliefs from much before the advent of organised religion? Does it symbolise the legends, thoughts and beliefs of the ancients? We may never know conclusively. What we do know for certain is that man roamed and inhabited this harsh and inhospitable high-altitude desert in centuries past, and these scattered rocks are probably the only imprint that remains of his presence.

The imagination soars in trying to derive meaning from the petroglyphs. Was this sacred art—expressions of spiritual beliefs from much before the advent of organised religion? Does it symbolise the legends, thoughts and beliefs of the ancients? We may never know conclusively. What we do know for certain is that man roamed and inhabited this harsh and inhospitable high-altitude desert in centuries past, and these scattered rocks are probably the only imprint that remains of his presence.

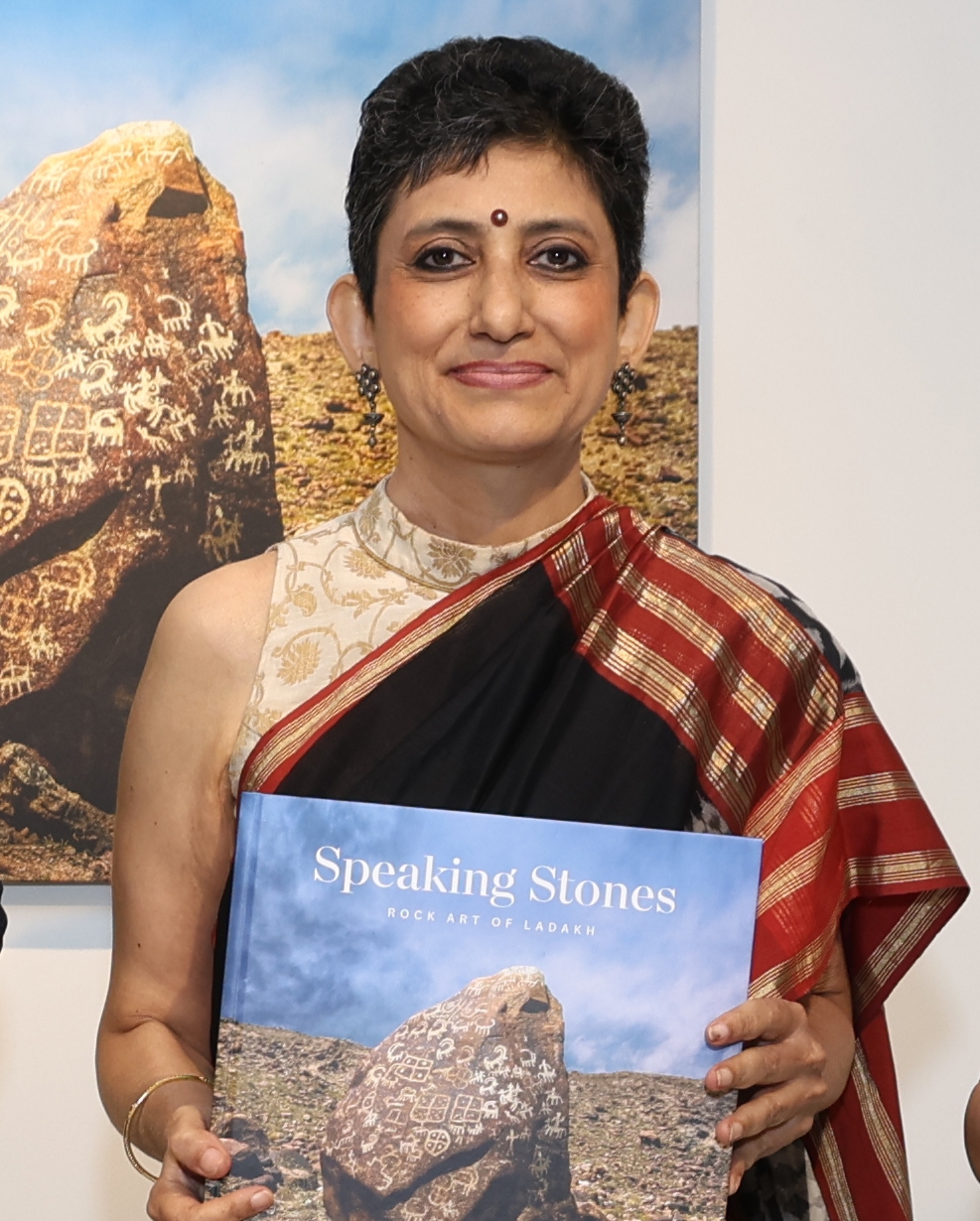

Beyond their historical and cultural value, what struck me most was the sheer artistry of these engravings—deliberate, stylised, and elegant. From deer with sweeping antlers to stick figures in joyous dance, and the arresting ‘Birthing Giant’ of Kargil, each form reflected a creative instinct as ancient as humanity itself. Even in Changthang—a region once thought devoid of rock art—I uncovered a site of striking significance. What began as a personal connection evolved into a larger effort to showcase these markings not just as archaeological artefacts, but as art—imbued with imagination, symbolism, and intent. Speaking Stones is my tribute to the unknown artists who once etched their truths into stone, and to the timeless bond between human expression and the land.

The threat over what has existed for millennia looms large. Many of these petroglyph sites lie exposed and unprotected, disappearing quickly under the pressure of road construction, development, and neglect. These open-air galleries need urgent protection if we are not to lose the only connection we have with our shared ancestral heritage. I’ve always believed that strong imagery holds the power to influence hearts and shift perspectives. Through this project, I wanted to create not just a visual record, but a quiet call to notice, to care. Because if we can’t see what’s vanishing, how do we begin to protect it?

In many uncanny ways, the arc of this project began to mirror the arc of my own life. As I walked ancient paths, the stones seemed to speak—not just of past lives, but of my own unfolding story. Through personal trials, including three cancer diagnoses during the course of this work, the landscape became both sanctuary and teacher. Long treks through Ladakh’s remote wilderness—days spent in silence, navigating raw terrain and sleeping under starlit skies—offered a healing deeper than any medication could. The drive to complete what I had started—this work I felt compelled and responsible for bringing to fruition—gave me a purpose that extended beyond the fears the disease had raised.

I wasn’t just seeking to document; I was seeking to understand, to feel, to remember something primal. These ancient rock galleries, scattered across ridges and riverbeds, held a presence that stilled the noise within. Time and again, I returned to them—not out of obligation, but because they offered a rare clarity. As the ego quieted, I found myself dissolving into something larger: moments of stillness, of sheer presence, where the “I” disappeared.

And in that emptiness, I began to feel whole.

When Speaking Stones was announced as a finalist for the 2024 Banff Mountain Book Award, I felt deeply grateful. But the real reward wasn’t the accolade—it was the inner transformation this journey sparked. In those sacred moments, I grasped something profound—that life, like the land, is always transforming, and nothing truly vanishes. The petroglyphs too, seemed to echo this truth. Though weathered and fading, their essence endures—marking a continuum of memory, creativity, and being. Nature, in all its rawness and grace, was both mirror and guide. And through this journey, I came home to myself.

And in that emptiness, I began to feel whole.

When Speaking Stones was announced as a finalist for the 2024 Banff Mountain Book Award, I felt deeply grateful. But the real reward wasn’t the accolade—it was the inner transformation this journey sparked. In those sacred moments, I grasped something profound—that life, like the land, is always transforming, and nothing truly vanishes. The petroglyphs too, seemed to echo this truth. Though weathered and fading, their essence endures—marking a continuum of memory, creativity, and being. Nature, in all its rawness and grace, was both mirror and guide. And through this journey, I came home to myself.

Just as these ancient artists once etched their truths into stone, I too have tried to leave a trace—not of ownership, but of reverence. A testament to our shared longing to connect—with land, with meaning, and with something eternal. This experience, with all its challenges and rewards, taught me that the most profound discoveries are not always those we seek, but those that reveal themselves unexpectedly. I consider myself fortunate to have been called to such a task—one that was challenging, captivating, and, above all, deeply rewarding.

All photos copyright Ahtushi Deshpande

All photos copyright Ahtushi Deshpande