WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BYAshna Ashesh

…To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go.

~ Mary Oliver

Hospital regulations require filling in the date and time in a Do Not Intubate (DNI) form, as if to record the exact moment you let go.

On April 10, 2024, at 1:10 pm, I signed my grandfather's form. I had spent almost a decade attempting to delay the inevitable, not knowing that one day I would have to help him embrace it.

You do everything you can to save a loved one, but you can't love someone out of dying. Love should be enough, but sometimes it isn’t. Nothing prepares you for that day. I am a lawyer and a public health professional. I knew a right to life with dignity includes a right to die with it. I knew my grandfather would not want to continue living hooked up to machines; alive but only technically so.

You do everything you can to save a loved one, but you can't love someone out of dying. Love should be enough, but sometimes it isn’t. Nothing prepares you for that day. I am a lawyer and a public health professional. I knew a right to life with dignity includes a right to die with it. I knew my grandfather would not want to continue living hooked up to machines; alive but only technically so.

No more ramming a tube down his throat.

No extreme measures.

My knowing was unshakable. Yet, a kind nurse had to steady my hand so I could fill out the form. Then I sat by my grandfather’s bedside, in the ICU, holding his hand. Because even though love isn't always enough, it's all we really have in life.

And in the end? Love is a trembling, warm hand holding a soon-to-be-cold one.

His laboured breathing, a ticking clock, the beeping of the cardiac monitor. Silence. It was the kind of silence that settles in your bones. My grandfather, who was once larger than life, now looked frail. In the moments following a loved one’s death, you enter a liminal space. Here, life as you knew it no longer exists, and the future is yet to arrive. Around me, doctors and nurses rushed to tend to the living. But I was in a room at the end of life.

I was the one who broke the news to my father. I knew my father would want me to be the one to break the news to him. “He’s gone. They did everything they could. He wasn't alone. I was with him,” I said. All true. Though what I really wanted to say was, “I’m sorry. He was struggling to breathe, and all I could do was hold his hand.” Also true.

But it's hard to say any of that when you have just had the wind knocked out of you, watching someone you love gasp for air. So, I didn't say it.

A week or so later, I confided in a friend. My friend, who claims he isn't very good with words or with grief, said, “Even in my faith, where some believe it is a sin to return life, what you did would be seen as an act of kindness.” I’m not a woman of faith, but in that moment, he gave me something I wasn't capable of giving myself: grace. It would be a while before I learnt I didn't need forgiving. He knew before I did. What he doesn't know to this day, though, is that his words held me in my grief the way a loved one's arms hold you, like they’re the only thing keeping you from falling apart. If he had met my grandfather, they would have gotten along like a house on fire. Unbelievably stubborn in their zest for living, even if it meant risking their lives—they had that in common. Effortlessly transforming the mundane into the magical, that too. They were both, simultaneously, the easiest and most annoying people to love. Their laughter could light up the darkest corners of a room, and when they left, the room itself would go quiet as though it had forgotten to exist. They had that effect on people, too.

In the months following my grandfather’s death, I travelled extensively for work. Delhi, Versoix, Bali—no matter where I went, a part of me was always in that room at the end of his life. How was I to inhabit this cavernous space, which had neither the warmth of the past nor the light of the future? Regardless of the time zone I was in, it was always 1:10 p.m. How was I to make meaning from barren moments? That’s the thing about end-of-life care decisions: the moment when you let go does not let go of you. The room at the end of life exists beyond what we know. At some point, one has to leave the room and venture farther into the unknown—an austere and arid interior landscape filled with the nothingness of loss.

Outside, it was summer. Delhi recorded its highest temperature in history. Oppressive heat, not even the rustle of leaves, until the day of that downpour. I was heading to my aunt’s house from the local tea shop when the rain began sheeting down. I took shelter under the canopy of an old friend, the neighbourhood Frangipani tree.

The Frangipani goes dormant in winter. Before it blooms, the tree appears to be on the verge of death. Now that it was summer, my friend was adorned with flowers: a reminder that sometimes what looks like death is but the beginning of blooming. A whole universe was birthed in nothingness, and we are too. The landscape of loss looks barren but is fallow. When the time comes, from this ground, the tender shoots of a new life will grow. Sometimes, people need to rest before their spirit can begin to rise. And sometimes that rest is found on foreign shores.

The Frangipani goes dormant in winter. Before it blooms, the tree appears to be on the verge of death. Now that it was summer, my friend was adorned with flowers: a reminder that sometimes what looks like death is but the beginning of blooming. A whole universe was birthed in nothingness, and we are too. The landscape of loss looks barren but is fallow. When the time comes, from this ground, the tender shoots of a new life will grow. Sometimes, people need to rest before their spirit can begin to rise. And sometimes that rest is found on foreign shores.

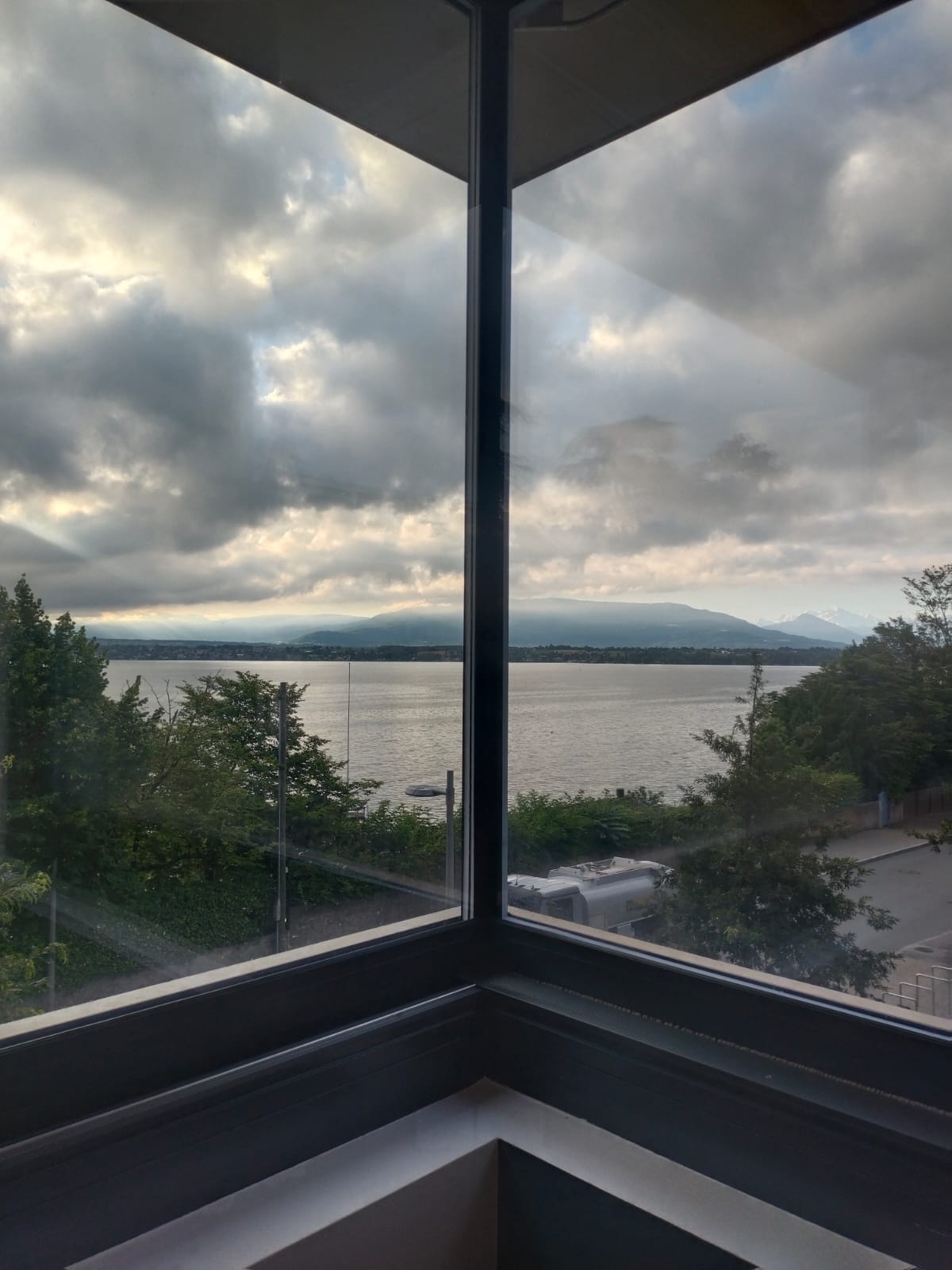

In June, I paused mid-swim to admire the early morning light dancing on the surface of Lac Léman in Versoix. Maybe it was the beauty of dawn or the buoyancy of water, but it was the first time since his death that I felt the lightness of my being. It was the first time I wasn’t afraid I would drown in my grief. I brought back pebbles from the bottom of the lake—keepsakes from the moment I came back to life.

It was a different life I came back to—one without him, one I did not know how to inhabit. The months that followed were a blur. The demands of daily living took over—a deluge of work. I was tending to my mother and then my dog, who were both sick. I was functioning on autopilot, relying on muscle memory.

Inside?

Untethered. Uprooted.

I blinked, and it was almost the end of the year. Another summer had come around. In November, I visited Bali for a conference and decided to extend my stay for a couple of days before returning home. I was reading under the canopy of a Frangipani tree—a lone, lambent star in the sky. Dogs were barking in the distance, and here, from the tree, a flower quietly fell to the ground. It is said the tree is native to Central and South America. Yet, far away from its ancestral home, the Frangipani is rooted in cultural myth and meaning across South-East Asian cultures. “It’s considered a symbol of immortality because it can flower and produce leaves even if uprooted.”* I picked up the fallen flower. It now lies pressed in the pages of a beloved book as a reminder that there are seasons for holding on and seasons for letting go; that we bloom even after we are uprooted; that the room at the end of life does not have to be the end of life as we know it.

I almost didn't write this story. It only exists because a friend convinced me otherwise. My grandfather loved stories. In the twilight years when dementia stole his memories, there were some stories that stayed—stories of the places he loved and the people who loved him. If there is an afterlife, I hope this story finds him and stays with him.

I could not love him out of dying, but in the wake of his death, I was loved into living. My father told me he found solace in the fact that I was with my grandfather in his last moments. Every time we spoke, a friend sang my name instead of saying it, as though my existence were an answered prayer, not the burden it felt like. She still does that, sings my name. A couple of friends and I spent countless evenings on calls together. We laughed till I cried. Shared laughter is the holiest sound in the world. The friend with faith enough for the both of us? Only one thing would annoy me more than his presence: his absence. I still don’t know how to live in a world without my grandfather and others I have lost. But I hope it's a big life with all of its seasons of loss and love.

And in the end?

I hope there is a warm hand to hold.

What more could one ask for?

* “In Blackwater Woods” by Mary Oliver, from American Primitive. © Back Bay Books, 1983.

* Plant of the Month: Frangipani, by Sean Wang Zi-Ming, available at https://daily.jstor.org/plant-of-the-month-frangipani/ (https://daily.jstor.org/plant-of-the-month-frangipani/)