Artisanal Toda Embroidery

Made available in limited numbers and designs for all seasons, no two pieces will ever be alike.

Explore

Each Toda-embroidered masterpiece is individually created by the few women-artisans of this small indigenous community of the Nilgiris practising this rare art.

Made available in limited numbers and designs for all seasons, no two pieces will ever be alike.

Issue 10

Home

“What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning.”

— T. S. Eliot

The word home embodies this paradox with ease.

It is where we begin, and the place that asks us to begin again. Sometimes it anchors us, arriving in fragments — a remembered doorway, a tree marking the turn of seasons, the taste of a childhood meal. At other times, it is simply the ground beneath our feet when everything else has changed. Home gathers the familiar and the faraway, the inherited and the improvised, the places we choose and the places that choose us.

All Issues

Kinship - Lost and Found

In a time when connection feels both omnipresent and strangely elusive, the essence of kinship can quietly slip from our grasp. As we navigate an increasingly fragmented world, this issue invites you to rediscover the hidden bonds that tether us—not just to one another but to the landscapes we inhabit and the larger ecosystem of life.

Kinship, in its truest sense, goes beyond the immediate; it recognizes the intricate web of relationships that shape us—through family, community, and the more-than-human world. The constellation of stories within this issue weaves these dimensions together, reminding us that belonging is not something we simply seek but something we continuously create.

Through essays, poetry, photography, illustrations, and personal narratives, Kinship—Lost and Found explores how these connections are sustained. How might we rekindle bonds with those we love and the animals we share the earth with? What wisdom can be gleaned from Indigenous elders who hold generations of knowledge about living in harmony with nature? How do we hold on to the spaces we once called home, the memories stirred by a well-worn family album, a treasured recipe, or the fleeting impulse of a familiar scent?

At the heart of these reflections is the understanding that kinship is never static—it is layered, dynamic, and evolving.

The Mountain Connection

An immersive exploration of the mountains around the world and their profound relationship with humanity.

How do we live within these grand landscapes, and how, in turn, do they live within us? “The Mountain Connection” travels from the majestic Himalayas, through the verdant Northeast, into the mystical heart of the Western Ghats, and to the far reaches of the Antarctic. Through exquisitely crafted stories we map the intricate bonds connecting these diverse terrains.

At the heart of this edition lie deeply reflective and thought-provoking themes spanning local and global perspectives. We delve into the myths and folklore that resonate across mountain ranges, asking what ancient wisdom the stoic rocks of distant peaks can impart.

Sensorium

Go beyond the ordinary to explore the captivating realm of sensory experiences—sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch—that define our daily lives.

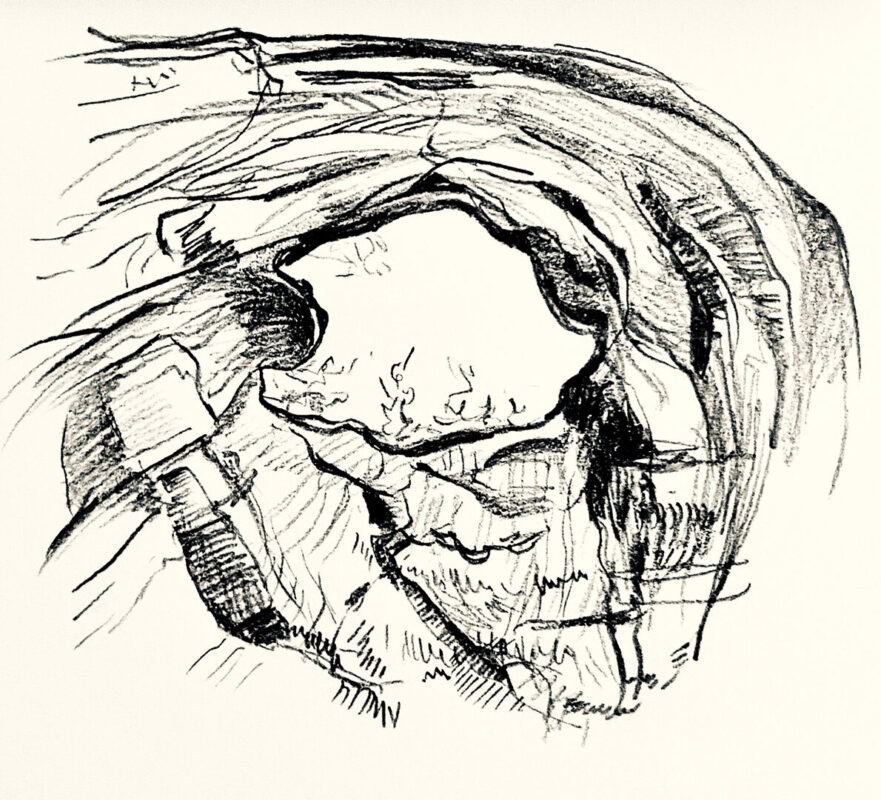

In this experiential issue titled “Sensorium”, we go beyond the ordinary to explore the captivating realm of sensory experiences—sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch—that define our daily lives. What is existence if not a ceaseless dance with our environment? Moment to moment, we interpret light as colours and images, discern music from noise, unearth flavors that delight the palate, encounter scents that uplift or overwhelm us, and discover new worlds with our fingertips.

As this issue arrives during the monsoons—a season full of sensory richness—we invite you to explore our carefully curated stories. Let the smell of wet earth, the sound of rain, and the brush of humid air enhance your reading. Additionally, if you prefer to listen, the stories are narrated by the authors who penned them.

Renewal

Embrace the pursuits of regeneration and restoration as we relinquish the old and usher in the new–invigorating our inner and outer worlds with a renewed sense of purpose.

Roots

Many facets of the theme “Roots”, encompassing seasonal symbolism, the practical reality of wintering underground, tales of provenance, heart and origin, and the natural world.

Gathering

Inspired by a time of year which is about the bringing together of people, memories, traditions, reflections, gifts, food, stories and so much more.

Monsoon Reflections

Monsoon Reflections showcases the many moods of human experience and of the season. It contains inspiring images of natural beauty and moving glimpses into many different walks of life, including our first long interview.

Summer Slowness

Summer Slowness is all about the Indian summer. You’ll find reflections on slow living, longing for rain and for the mountains, the pleasure of scents and books – and more – in the words, images, videos and music curations that we have to offer.

Issue 9

Listening to Life

What does it mean to listen—with attention, presence, and intention?

Listening is more than hearing. It is noticing the hush that settles over a landscape just before rain, or the way a child pauses before speaking, searching for the right shape of a thought. It is attuning ourselves to rhythm and breath, memory and feeling, to what gently flickers just beneath spoken words. It is not passive but deeply relational, connecting us to one another, to the places we inhabit, to the movements of time, and to the subtle unfolding of our lives.

In a world flooded with alerts, chatter, and constant noise—where speed is prized over depth—listening becomes an act of resistance. It often begins quietly, perhaps in a moment of stillness when something within us leans toward something outside. Sometimes it arises through rupture—in the wake of loss or change—as the familiar falls away and we discover new meanings or overlooked voices.

Listening asks us not merely to notice, but to linger, staying long enough to allow ourselves to be changed.

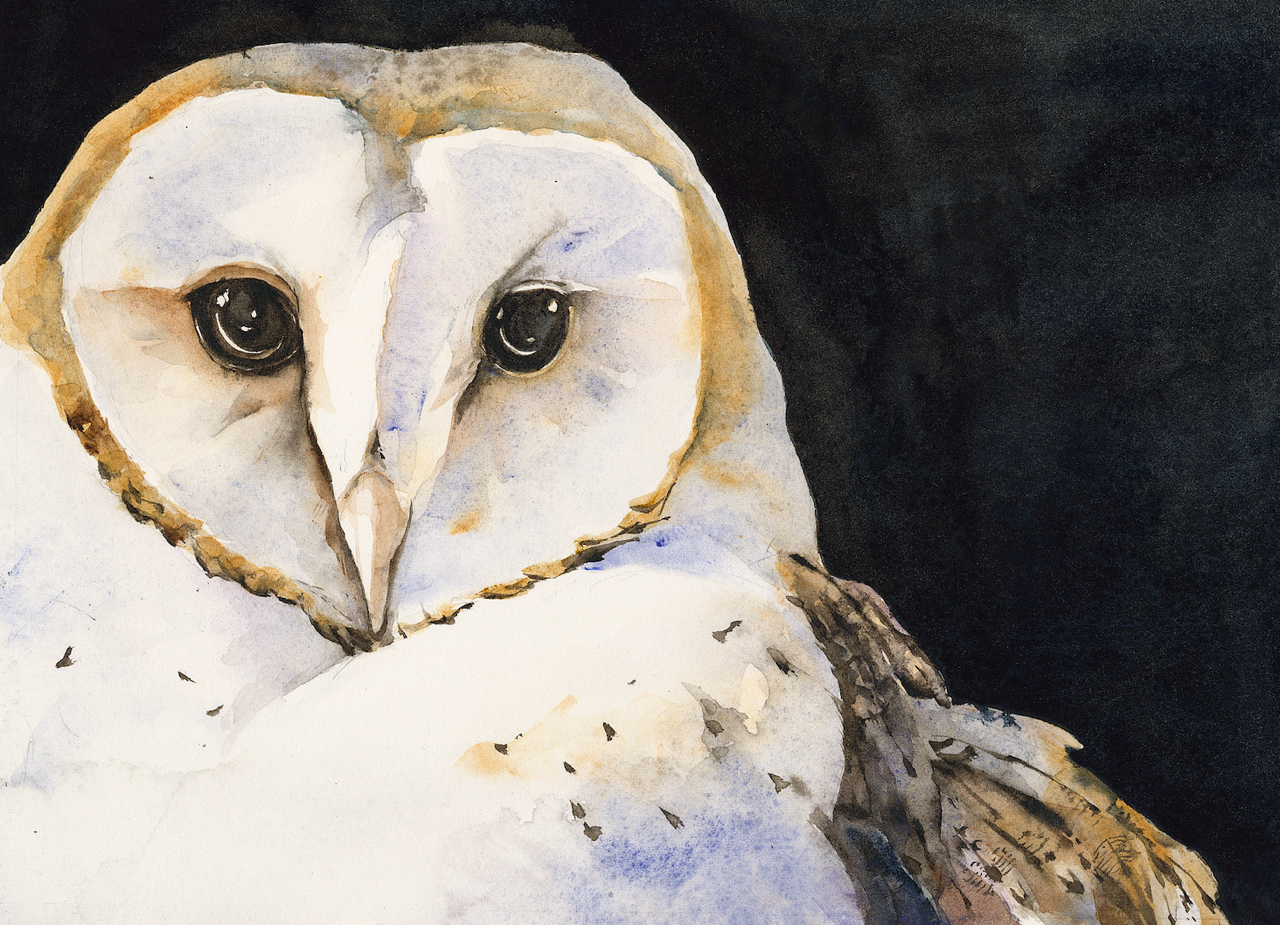

Searching For Peace

BY Jackie Morris

A Songline in the Elephant Hills

BY Divya Mudappa, T. R. Shankar Raman

Listening to Trees: A Circle of Life

BY Priyanka Sacheti

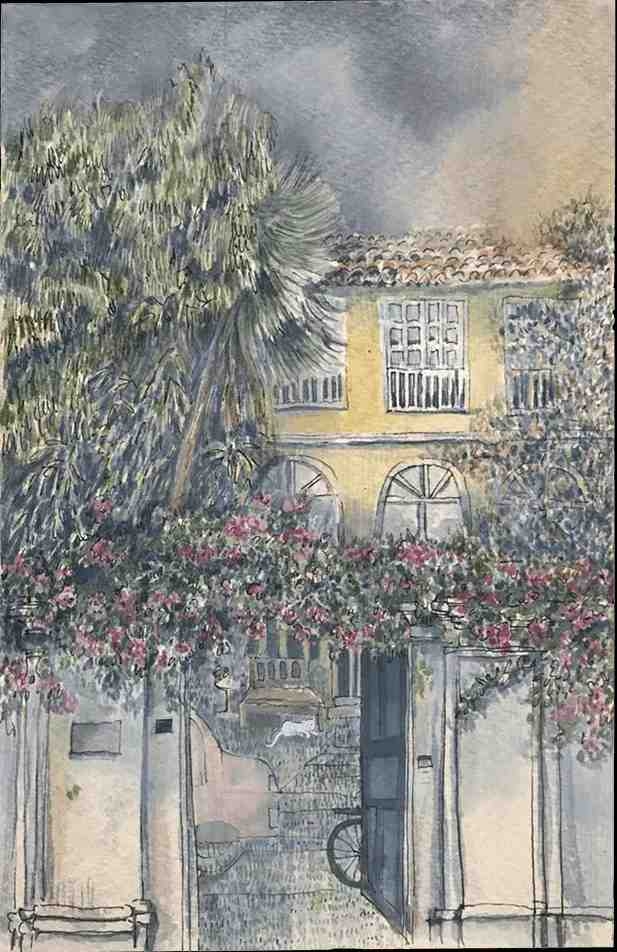

The House by the River

BY Parvathi Nayar

How Stories Arrive: Geeta Ramanujam on Listening

BY Ramya Reddy

Issue 9: An introduction

BY Ramya Reddy

What do I Know From?

BY Shastri Akella

Issue 8

Kinship - Lost and Found

In a time when connection feels both omnipresent and strangely elusive, the essence of kinship can quietly slip from our grasp. As we navigate an increasingly fragmented world, this issue invites you to rediscover the hidden bonds that tether us—not just to one another but to the landscapes we inhabit and the larger ecosystem of life.

Kinship, in its truest sense, goes beyond the immediate; it recognizes the intricate web of relationships that shape us—through family, community, and the more-than-human world. The constellation of stories within this issue weaves these dimensions together, reminding us that belonging is not something we simply seek but something we continuously create.

Through essays, poetry, photography, illustrations, and personal narratives, Kinship—Lost and Found explores how these connections are sustained. How might we rekindle bonds with those we love and the animals we share the earth with? What wisdom can be gleaned from Indigenous elders who hold generations of knowledge about living in harmony with nature? How do we hold on to the spaces we once called home, the memories stirred by a well-worn family album, a treasured recipe, or the fleeting impulse of a familiar scent?

At the heart of these reflections is the understanding that kinship is never static—it is layered, dynamic, and evolving.

The Colour of Remembering

BY Pankaj Singh

Pathways into Kinship: Lessons on Belonging from the Monarch Butterfly

BY Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder, Athulya Pillai

Co-Becoming: The Human-Dog Kinship

BY Sindhoor Pangal

Wildflowers, Rivers, and Mountains—Navigating Time and Kinship

BY Shrishtee Bajpai

The Old Dog in the Kitchen

BY Smriti Rana

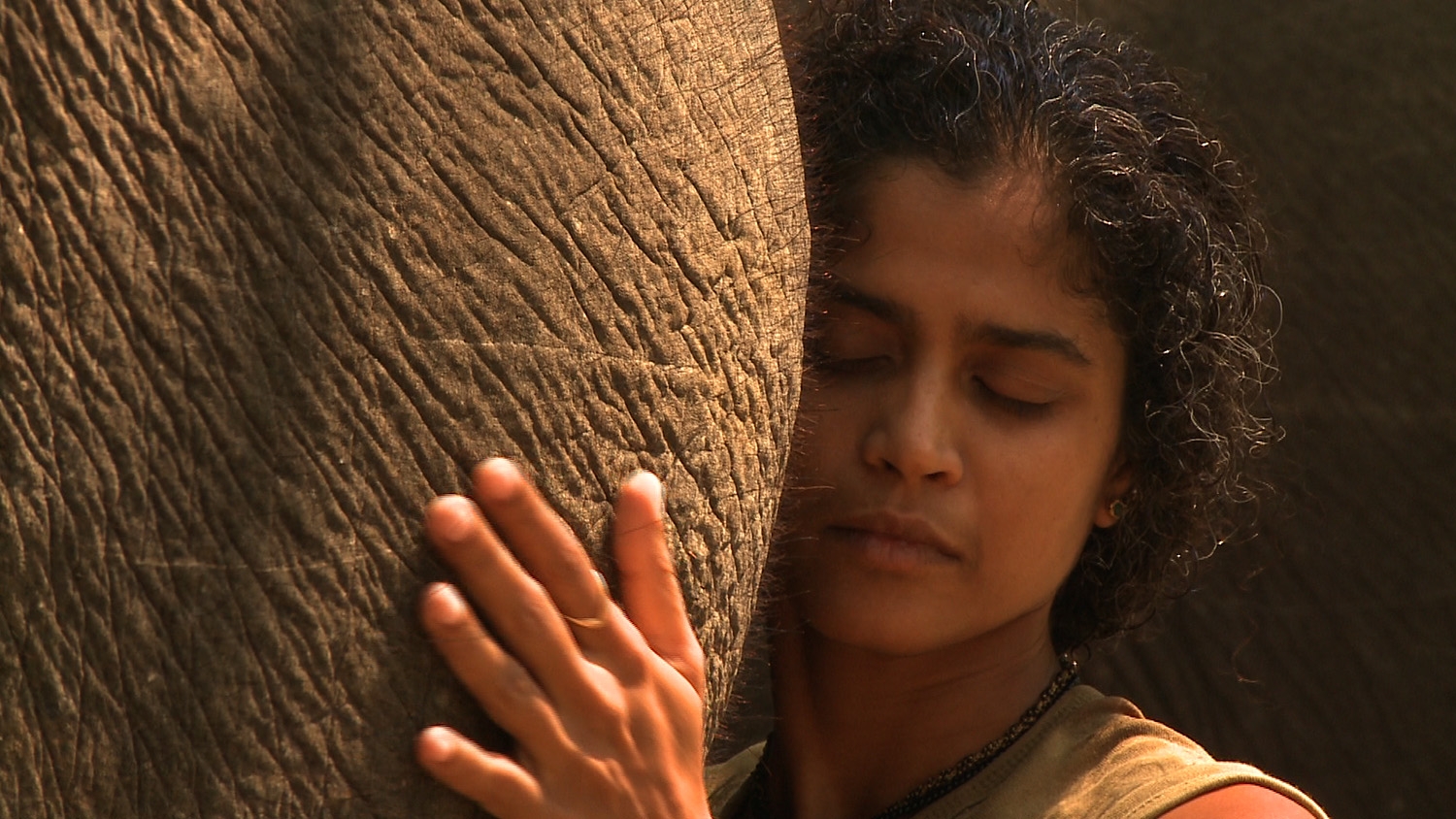

A Life Walking with Elephants: In Conversation with Prajna Chowta

BY Prajna Chowta, Ramya Reddy

Craft in South India: A Legacy at the Crossroads

BY Deborah Thiagarajan, Rekha VijayaShankar

The Keeper of Indigenous Memory: Remembering Janagiamma

BY Ramya Reddy

Broken By Bread

BY Janaki Ranpura